In our current Core III Environmental Sustainability class, we've considered the western relationship with a growing China, and what that means for the future of democracy and freedom on planet earth, especially in the light of climate change.

One take-home message is that an undemocratic and corrupt China is unlikely to be a good partner in reducing emissions, yet western emissions reductions alone cannot contain climate change in the absence of China.

Elsewhere, I've proposed an international "free trade" zone for climate-compliant countries, who would then charge tariffs on non-compliant ones. This seems, to my mind at least, to be the best, most active approach for the west. I don't think we can afford to be passive.

Another approach, not mutually exclusive, is to take every opportunity to foment real democracy in China, on the assumption that this would eventually be good for the climate. The Chinese people, who are tired of their corrupt and kleptocratic leaders, and have a deep desire for social fairness, are our best allies in this.

This isn't a trivial notion. Under normal circumstances, there's no internal political peace in China without the Confucian "mandate of heaven" -- which could be translated in today's propagandistic world as, if you want to rule China, you need to at least be sure that the majority of people are willing to "suspend their disbelief" in the proper authority of the government to rule.

According to Scottish-born Harvard historian Niall

Ferguson, whose film we watched, the alternative is 动荡 -- Dòngdàng, or

turmoil, such as occurred in 1989 in Tiananmen Square.

Even Mao, who famously praised the "earthy" culture of ordinary Chinese

people, understood the power of the mass movement in China, and used it

to considerable effect for his own gain during the Cultural Revolution,

effectively setting the youth of the country against the elders, in an

amazing upturn of traditional values that is almost impossible for

westerners to comprehend. The social and cultural repercussions

reverberate yet. A horrific case in point is the front page feature in

the Guardian today.

This is what the Chinese leadership is most afraid of, says Ferguson. Everything else follows from this. And China may be on the brink. Regular protests against local and regional corruption are suppressed, but still occur. The government worries that these could eventually combine in a democratic opposition, a "Chinese spring."

The new president, Xi Jinping, has ordered at least a window-dressing approach to reducing corruption. Conspicuous display is now, apparently, officially discouraged. The change has come swift and fast. He's only been in office a few weeks.

It remains to be seen how deep this reform goes.

Perhaps not too deep. According to the conclusion of the NYT article linked above, and confirmed elsewhere, the saying among the elite is now, "Eat quietly, take gently and play secretly."

Here at Sustainability T & D, we'll be watching to see what happens, since the future of the planet depends on a China that can be dealt with on some rational basis.

We prefer democracy and reason, but we'll settle for reason.

Thursday, March 28, 2013

Tuesday, March 26, 2013

The "Black Dog Institute"

I know mental illness isn't usually one of my topics, but to be honest, the worries I normally post about are enough to drive anyone to depression.

But I did once spend a fairly long stint in a past life working with troubled youth as a house counselor and adventure therapy instructor, so I do have some experience and training in this regard. And I have posted on the problems of despair and of mental health approaches to reducing consumerism.

I'm also very interested in Winston Churchill and have a large collection of books on the subject. I'm attracted to his very colorful personality, probably the most important human being in 20th century history. But his was also a very complex and multifaceted personality. His warnings about the increasing threat from Hitler in the 1930s, the era of appeasement, remind me of current events in climate denial. This took incredible vision and stoicism. And he was able to maintain outwardly high morale and indeed pure defiance in the face of the Nazi threat in 1940. All this, despite occasionally slipping into what he called his "black dog."

You can't help but be fascinated and even sympathetic. Some people manage to do great things in spite of mental health difficulties.

So I was immediately interested when a friend posted about the "Black Dog Institute," an Australian non-profit that helps people suffering from bipolar and mood disorders, and depression, using expeditions and other adventure therapy approaches, named of course after Churchill's "black dog".

I'd never heard of it.

Very cool. Almost makes me want to become depressed.

But I did once spend a fairly long stint in a past life working with troubled youth as a house counselor and adventure therapy instructor, so I do have some experience and training in this regard. And I have posted on the problems of despair and of mental health approaches to reducing consumerism.

I'm also very interested in Winston Churchill and have a large collection of books on the subject. I'm attracted to his very colorful personality, probably the most important human being in 20th century history. But his was also a very complex and multifaceted personality. His warnings about the increasing threat from Hitler in the 1930s, the era of appeasement, remind me of current events in climate denial. This took incredible vision and stoicism. And he was able to maintain outwardly high morale and indeed pure defiance in the face of the Nazi threat in 1940. All this, despite occasionally slipping into what he called his "black dog."

You can't help but be fascinated and even sympathetic. Some people manage to do great things in spite of mental health difficulties.

So I was immediately interested when a friend posted about the "Black Dog Institute," an Australian non-profit that helps people suffering from bipolar and mood disorders, and depression, using expeditions and other adventure therapy approaches, named of course after Churchill's "black dog".

I'd never heard of it.

Very cool. Almost makes me want to become depressed.

Classic weakened AO caused by ice loss

We'll discuss this new paper in class:

Jennifer A. Francis and Stephen J. Vavrus,

Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather

Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather

The grave difficulty with this new finding, if corroborated, is that the deeper oscillations, even though they will contribute to severe weather events, will also likely appear to most people in the US and UK as "global cooling. This despite the fact that the planetary and northern hemisphere AAT will have warmed.

This will add to our difficulties getting a sensible climate policy, especially if other results suggesting a lower, narrower band for climate sensitivity are also replicated from multiple different approaches.

This will add to our difficulties getting a sensible climate policy, especially if other results suggesting a lower, narrower band for climate sensitivity are also replicated from multiple different approaches.

Fracked gas to heat UK homes by 2018. Is this a major geopolitical shift?

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/mar/25/us-shale-gas-british-homes-five-years

See also, earlier,

See also, earlier,

Pipeline failure highlights energy insecurity in UK

Big tanker eases UK fuel shortage worries

and

Cyprus bailout: Kremlin 'could punish Europe' in reprisal for bank levy

We'll have to discuss these linked events in class when students return.

Does this mean that the large new supplies of domestic energy in the US are changing the geopolitical equation? What does in mean for the US ability to project power and prestige that Europe's winter gas woes are (eventually) to be relieved by US supplies? How likely is it that any US Presidential administration or party, Republican or Democrat, will act against fracking in the US, given the geopolitical stakes? What difference does it make that the time horizon is so long for gas delivery planning?

Big tanker eases UK fuel shortage worries

and

Cyprus bailout: Kremlin 'could punish Europe' in reprisal for bank levy

We'll have to discuss these linked events in class when students return.

Does this mean that the large new supplies of domestic energy in the US are changing the geopolitical equation? What does in mean for the US ability to project power and prestige that Europe's winter gas woes are (eventually) to be relieved by US supplies? How likely is it that any US Presidential administration or party, Republican or Democrat, will act against fracking in the US, given the geopolitical stakes? What difference does it make that the time horizon is so long for gas delivery planning?

Monday, March 25, 2013

Sunday, March 24, 2013

Rosenthal on an "all-in green" energy policy

A short, interesting perspective. In today's New York Times.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/sunday-review/life-after-oil-and-gas.html?src=recg

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/sunday-review/life-after-oil-and-gas.html?src=recg

Saturday, March 23, 2013

Pipeline failure highlights energy insecurity in UK

The closure of a cross-channel natural gas pipeline has highlighted the terrific insecurity of the UK's energy supplies since North Sea gas began to dwindle. The UK is increasingly at the mercy of continental suppliers, who themselves sit at the end of a interlinked chain-of-effect that begins in Russia, where kleptocrats and authoritarians run the energy business, and are perfectly willing to hold the hapless Europeans hostage for energy supplies.

You'd have to read between the lines and be as steeped in (some would say besotted by) industrial history as I am to get the full meaning of this seemingly small event, but this is a pretty pass for a country that was an net energy exporter until just a few years ago. The proud history of domestic UK energy is also the history of the Industrial Revolution, and goes back to the first days of steam power in the coal mines of the north and west of the country. The first combustion engines were designed primarily to pump water out of these mines so we could get at the coal. From these beginnings we got the industrial system here in New England -- built largely with British capital and know-how. Without those New England mills, and some bloody-minded northern agitators, America might still be a slave-holding society. Without the extension of Yankee industry into the midwest, building plant like the famous Willow Run B24 line, Germany might still be in charge of Europe.

More recently, the North Sea, run from Aberdeen, Tyneside and Hull, was the birthplace of the offshore energy industry generally, and lessons learned on the rigs were put to work building the great offshore wind farms now under construction.

There seems a small salvation for our former and perhaps future western industrial might. One source of domestic energy that has stepped into the breach since the closure of the gas pipeline is that UK wind. It's windy there right now. With over five thousand turbines, including a growing number of (relatively) less intermittent offshore plants, the UK's wind energy system is able to cover some for the temporary slowing of gas supplies, at least that part of them that was producing electricity.

This is one of the great things about wind energy -- it comes in the winter, at least in the north Atlantic region, which is when we need the energy most. We very badly need to build more of it, if we are to cherish our freedom and avoid the worst of climate change.

This is particularly true in Britain. The British Isles and Eire comprise a long archipelago oriented north-south, beginning at a latitude well above Maine and continuing to just a few degrees shy of the Arctic circle. The islands get lashed by North Atlantic weather systems from autumn to spring equinox, and much of the winter is gloomy and stormy. Solar power doesn't work very well there in winter. When I lived in the north of Scotland, there were days when it wouldn't really get light at all in December, if the weather was at all cloudy.

Here in the US, although we're further south and so have more scope for solar power, these trade-offs still exist, but you wouldn't know it from the low intellectual quality of the energy debate so far.

How many of Maine's anti-wind activists are pro-fracking?

How many of Maine's anti-fracking campaigners are pro-wind?

Or are they all just pro-NIMBY?

You'd have to read between the lines and be as steeped in (some would say besotted by) industrial history as I am to get the full meaning of this seemingly small event, but this is a pretty pass for a country that was an net energy exporter until just a few years ago. The proud history of domestic UK energy is also the history of the Industrial Revolution, and goes back to the first days of steam power in the coal mines of the north and west of the country. The first combustion engines were designed primarily to pump water out of these mines so we could get at the coal. From these beginnings we got the industrial system here in New England -- built largely with British capital and know-how. Without those New England mills, and some bloody-minded northern agitators, America might still be a slave-holding society. Without the extension of Yankee industry into the midwest, building plant like the famous Willow Run B24 line, Germany might still be in charge of Europe.

More recently, the North Sea, run from Aberdeen, Tyneside and Hull, was the birthplace of the offshore energy industry generally, and lessons learned on the rigs were put to work building the great offshore wind farms now under construction.

There seems a small salvation for our former and perhaps future western industrial might. One source of domestic energy that has stepped into the breach since the closure of the gas pipeline is that UK wind. It's windy there right now. With over five thousand turbines, including a growing number of (relatively) less intermittent offshore plants, the UK's wind energy system is able to cover some for the temporary slowing of gas supplies, at least that part of them that was producing electricity.

This is one of the great things about wind energy -- it comes in the winter, at least in the north Atlantic region, which is when we need the energy most. We very badly need to build more of it, if we are to cherish our freedom and avoid the worst of climate change.

This is particularly true in Britain. The British Isles and Eire comprise a long archipelago oriented north-south, beginning at a latitude well above Maine and continuing to just a few degrees shy of the Arctic circle. The islands get lashed by North Atlantic weather systems from autumn to spring equinox, and much of the winter is gloomy and stormy. Solar power doesn't work very well there in winter. When I lived in the north of Scotland, there were days when it wouldn't really get light at all in December, if the weather was at all cloudy.

Here in the US, although we're further south and so have more scope for solar power, these trade-offs still exist, but you wouldn't know it from the low intellectual quality of the energy debate so far.

How many of Maine's anti-wind activists are pro-fracking?

How many of Maine's anti-fracking campaigners are pro-wind?

Or are they all just pro-NIMBY?

Thursday, March 21, 2013

New DoE Energy Literacy push

The DoE has a new booklet out on energy literacy, and will soon be promoting an Energy 101 standardized course for undergraduates.

A good idea, long overdue.

A good idea, long overdue.

Growth, the deficit, green jobs, and the steady-state economy

I made the big mistake of commenting on a former student's Facebook post, in which he bemoaned the deficit, as many young people are doing recently, taking the view promoted by many politicians that the current high deficit and national debt in the US amounts to an unfair deal for younger people and future generations.

This was a mistake on my part, because there isn't really the ability on Facebook to get down to economic evidence and reasoning. I got the usual kind of Facebook shout-fest for my troubles. I should have known better.

Still, as an educator, this is a teachable moment, and so I can't just abandon the field. I chose instead to put my views in writing here on my blog, where I can show proper graphics and explain myself at length. Arguably, this is a retreat. But I don't care to play the game the way it's normally played, with people yelling at one another in short, rude, Facebook blurbs and tweets, so here goes.

The reason I don't believe that the current US deficit and national debt are that important in the large scheme of things is because the absolute value of a deficit is not the proper economic measure to use when evaluating whether or not it can be easily repaid. Instead, we have to use a relative value. The debt has to be compared to national income and to the prevailing rate of interest.

Indeed, this is what will happen if a consumer applies for a mortgage or a car loan. It doesn't matter whether it's a second-hand Chevy Aveo or a nice new BMW, the bank will only make the loan if the individual's debt to income ratio meets certain income parameters. In deciding the threshold, they take the interest rate into account.

In the case of the current (annual) US deficit and (total) national debt, both are actually at surprisingly moderate levels, compared to the now-growing US GDP. Here's the relevant graphics, starting with the national debt:

Click on the graphic to enlarge it. This chart was first published in The Atlantic late last year, to accompany a nice, solid article on the debt by Matthew Philips. Both the article and the chart paint a different story than you'll get from listening to politicians. I recommend you read it, especially before responding to this post. Basically, the baby-boomers inherited a much larger debt, proportional to their ability to pay, than the current older generation is leaving the young.

You can see from the graph that at around 63%, the current dept/GDP ratio is high, the second highest ever, but only about 15% points above the Reagan-era figure. Reagan's debt went mostly to pay for US military expansion, which boosted the economy, creating what a lot of progressive economists call, tongue-in-cheek, "militarized Keynesianism." (Allegedly, the only kind of economic stimulus Republicans like, but a stimulus nevertheless, whose employment proves the point that Keynesian fiscal stimulus does work.)

We began to pay that particular used car off quite nicely once growth and more moderate government took over again in the 1990s. Low oil prices and the dot com boom helped.

And the bank, which in this case means the international bond holders that hold US government debt, believes that the whole thing is quite a decent investment, and rewards us with historically low interest rates on these bonds, lower indeed than the Reagan era ones.

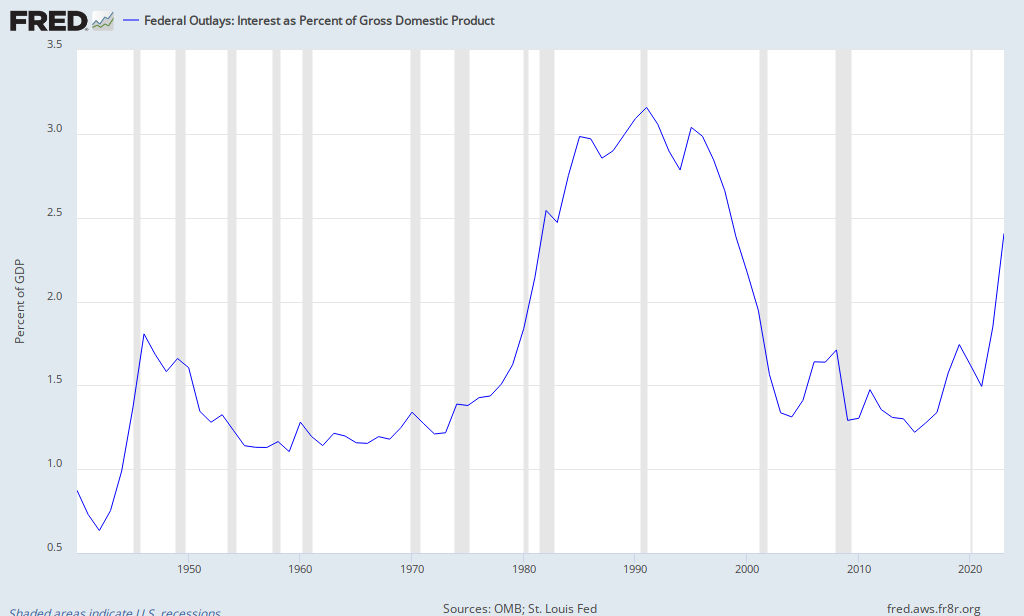

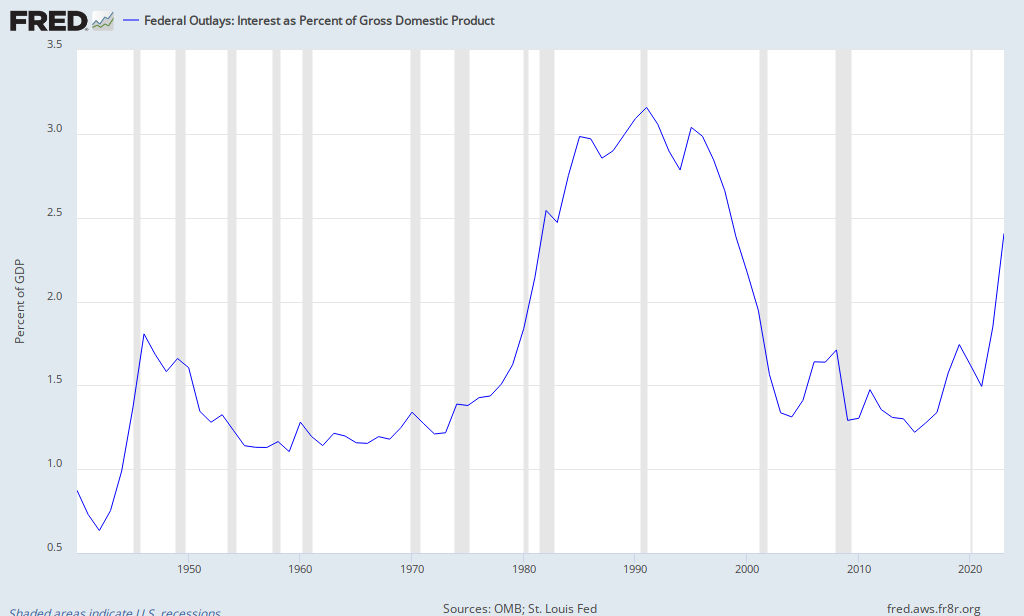

In other words, global capitalists aren't at all worried about the deficit. If they were, interest rates on US bonds would rise. But they are at the lowest levels in a generation. Here's the relevant data, again total interest outlay is showed proportional to GDP:

What this means is that we should have been several times more worried about the deficit in the Reagan era than we are now. Instead the opposite is more likely true for most young people, given all the misinformation circulating about the debt right now.

As for the current account deficit to GDP ratio, that has been improving nicely since the end of the most recent significant round of fiscal stimulus, the ARRA, in 2011. In the graph below, a balanced budget is represented by the zero line, a deficit is a negative value, and a surplus a positive value. The uptick at the end is our current improving situation.

You can also see that the US had a deficit nearly every year since 1948. How could we afford this? Well, because GDP growth and inflation essentially made the deficit affordable. And, although the recent deficits have been large, at least since WWII, we are again reducing them quite nicely.

Who is actually paying down the current account deficit? Well, other than GDP growth, which is actually the major part of the decrease, those of us who have had our taxes raised recently are paying it down, especially older people who have career jobs that pay relatively well, and those of us who are receiving fewer services since the recent sequester. I'm no billionaire, but I'm now paying over a hundred dollars a month more in federal taxes than I was three months ago. And the recent announcement that some of the tourist roads in Acadia NP will open later than usual because of the sequester is just one example of where the savings are coming from. This will, of course, be the second major US debt boom that I've helped pay off, the first being the one in the 1990s.

This is essentially what happens if a young couple buys a house on a typical 20-30 year fixed-interest mortgage and lives in it thriftily for the rest of their lives. The payments will seem high at the beginning. But by the end of the process, inflation and income growth will have reduced their importance in the family budget. By the time the mortgage is paid off, years ahead of time, it won't even be a very big bill in the general scheme of things. If at the same time, they reduce other bills, they might even make double payments on the mortgage.

And so, if the national-level process follows the established pattern since 1945, the deficit will be reduced to a manageable negative three to five percent within a few years here, perhaps sooner, while the debt itself will go away over a longer period of time, although never completely. The total debt level is in fact not that important once the correct deficit to GDP ratio is reestablished. And most of this will be achieved by the new tax hikes and spending cuts already in the pipeline, which don't really make a big difference to younger people at the beginning of their careers, unless they are already making large salaries.

Hence, by the way, Speaker of the House Beohner's recent confession on national TV that the palaver over the debt and deficit is just that, palaver.

None of this rational argument is going to make a big dint in the pessimism of a member of the younger generation who has fallen victim to the recent, mostly right-wing propaganda about the debt and deficit. I'm getting too long in the tooth to expect that propaganda goes away just because some professor proves it bull with a few statistics. The viral meme is just too strong. But I expect that the fuss will die down over the next few years, as fussing about the debt drops off the national radar a little at a time.

What was interesting about my Facebook exchange was that this particular alumnus's pessimism was compounded by the addition of climate change to his Calculus of Doom. This is of course not usually a concern for the right wing in US politics. But I can see how someone might be lured into seeing them as part and parcel of the same rigged scheme, youth versus age.

Essentially, in this view, the older generation is sticking the younger one with both a large un-payable debt and a deteriorating climate.

OK. Now there's one point there I can at least in part agree with. If we don't do something rational about climate change soon, we will have stuck the younger generation with a terrible burden.

But what's the solution? And what is the relationship of the solution to the federal debt and to Keynesian economics?

There are essentially two economic roads out of the climate crisis. One is to adopt a strong ecological economics prescription of low or zero growth, a Dalian steady-state economy.

The other is to grow a green energy economy, which would also grow GDP, to essentially continue on the current pathway of growth economics, only to replace dirty energy sources with green ones.

Certainly we're in trouble with the deficit if we adopt a zero growth plan. Without GDP growth, the deficit and debt will remain large in comparison to GDP, and would be very hard to pay off. A low or zero growth plan will also require unimaginably large programs of social reeducation (to reduce the power of consumerism) and a huge reevaluation of the idea of work in American society (the small amount of remaining work would have to be much more equally shared out) if it isn't going to look and feel like a horrible depression.

But we're almost certainly not going to choose this option anyway.

Particularly given the most recent political climate in the US, the same political climate that produced the deficit propaganda this former student is swallowing, I don't for a minute imagine that American society is ready to give up on growth economics and reevaluate consumerism and employment as foundations for society. That's just too much to ask.

This plan would also require an almost impossible level of public education regarding the dangers of climate change and other sustainability problems, as well as complete revision of the American mythology about capitalism. It just isn't very likely to happen anytime soon.

Even though I studied under Daly, and even though I think ecological economics is a great scientific improvement over neo-classical and even Keynesian economics, and even though I would like to see the world begin to move towards acceptance of the steady-state reasoning that you can't grow an economy forever on a finite planet, I understand that explaining this notion to the American people right now is going to be very, very difficult to do.

But I don't think that business-as-usual capitalism is a safe pathway, either. That will almost certainly result in the kind of damage ot the climate and to planetary ecosystems that this alumus is worried about.

What I think might succeed in the current political environment is a kind of green Keynesianism, whereby we learn to invest in renewable energy not just as the solution to climate change, but as a green economic stimulus. This has the added advantage of supporting global democracy. It's a lot better for the domestic economy and for global democracy if we spend our energy dollars internally on solar power and wind power and energy efficiency, than if we give those dollars to the world's various and multiple petrostate dictatorships.

But this plan might call for more, not less fiscal stimulus, especially if the economic model used required a lot of government intervention to set up the correct market conditions. It might even add to the deficit, at least in the short term.

If you put me in charge of the US government, I'd probably run up the deficit over several years to pay for some serious energy research and a lot of renewable energy and energy efficiency measures, all to prevent climate change!

I'd be careful not to run it up more than we could afford to pay for on the proceeds of the very large domestic energy and reconstruction boom we would then have.

But I'd run it up nevertheless.

Of course, this idea is a non-starter too, at least without a major change in US politics.

One other notion that received at least some bipartisan support a while back, even (for a very short while) from the irrepressible deficit scold himself, Grover Norquist, is that we might reduce climate emissions in a deficit-neutral manner by using a carbon tax to switch incentives around within the economy, to reduce the amount of government investment needed by using private money in response to market-based incentives.

Tax fossil fuels, subsidize renewables and efficiency.

You could, if you were really clever, even use the carbon tax to begin to pay down the debt.

Now there's a thought. Two birds with one stone.

Of course, thinking complex thoughts like this about the climate crisis and the American electorate requires a considerable amount of economic and political science education. And not just about ordinary or mainstream economics. Young people should be given the facts about climate change, as well as an education in these three competing economic models, and then even asked to evaluate a Dalian zero growth or steady-state model against this green Keynesian model.

We cover all this in our Unity College economics classes, and even in our required Core III Environmental Sustainability class.

I do believe, though, that my own sophistication about these ideas has probably grown since this particular student was in any of my classes.

I certainly I don't expect we'll get there on Facebook.

This was a mistake on my part, because there isn't really the ability on Facebook to get down to economic evidence and reasoning. I got the usual kind of Facebook shout-fest for my troubles. I should have known better.

Still, as an educator, this is a teachable moment, and so I can't just abandon the field. I chose instead to put my views in writing here on my blog, where I can show proper graphics and explain myself at length. Arguably, this is a retreat. But I don't care to play the game the way it's normally played, with people yelling at one another in short, rude, Facebook blurbs and tweets, so here goes.

The reason I don't believe that the current US deficit and national debt are that important in the large scheme of things is because the absolute value of a deficit is not the proper economic measure to use when evaluating whether or not it can be easily repaid. Instead, we have to use a relative value. The debt has to be compared to national income and to the prevailing rate of interest.

Indeed, this is what will happen if a consumer applies for a mortgage or a car loan. It doesn't matter whether it's a second-hand Chevy Aveo or a nice new BMW, the bank will only make the loan if the individual's debt to income ratio meets certain income parameters. In deciding the threshold, they take the interest rate into account.

In the case of the current (annual) US deficit and (total) national debt, both are actually at surprisingly moderate levels, compared to the now-growing US GDP. Here's the relevant graphics, starting with the national debt:

Click on the graphic to enlarge it. This chart was first published in The Atlantic late last year, to accompany a nice, solid article on the debt by Matthew Philips. Both the article and the chart paint a different story than you'll get from listening to politicians. I recommend you read it, especially before responding to this post. Basically, the baby-boomers inherited a much larger debt, proportional to their ability to pay, than the current older generation is leaving the young.

You can see from the graph that at around 63%, the current dept/GDP ratio is high, the second highest ever, but only about 15% points above the Reagan-era figure. Reagan's debt went mostly to pay for US military expansion, which boosted the economy, creating what a lot of progressive economists call, tongue-in-cheek, "militarized Keynesianism." (Allegedly, the only kind of economic stimulus Republicans like, but a stimulus nevertheless, whose employment proves the point that Keynesian fiscal stimulus does work.)

We began to pay that particular used car off quite nicely once growth and more moderate government took over again in the 1990s. Low oil prices and the dot com boom helped.

And the bank, which in this case means the international bond holders that hold US government debt, believes that the whole thing is quite a decent investment, and rewards us with historically low interest rates on these bonds, lower indeed than the Reagan era ones.

In other words, global capitalists aren't at all worried about the deficit. If they were, interest rates on US bonds would rise. But they are at the lowest levels in a generation. Here's the relevant data, again total interest outlay is showed proportional to GDP:

What this means is that we should have been several times more worried about the deficit in the Reagan era than we are now. Instead the opposite is more likely true for most young people, given all the misinformation circulating about the debt right now.

As for the current account deficit to GDP ratio, that has been improving nicely since the end of the most recent significant round of fiscal stimulus, the ARRA, in 2011. In the graph below, a balanced budget is represented by the zero line, a deficit is a negative value, and a surplus a positive value. The uptick at the end is our current improving situation.

You can also see that the US had a deficit nearly every year since 1948. How could we afford this? Well, because GDP growth and inflation essentially made the deficit affordable. And, although the recent deficits have been large, at least since WWII, we are again reducing them quite nicely.

Who is actually paying down the current account deficit? Well, other than GDP growth, which is actually the major part of the decrease, those of us who have had our taxes raised recently are paying it down, especially older people who have career jobs that pay relatively well, and those of us who are receiving fewer services since the recent sequester. I'm no billionaire, but I'm now paying over a hundred dollars a month more in federal taxes than I was three months ago. And the recent announcement that some of the tourist roads in Acadia NP will open later than usual because of the sequester is just one example of where the savings are coming from. This will, of course, be the second major US debt boom that I've helped pay off, the first being the one in the 1990s.

This is essentially what happens if a young couple buys a house on a typical 20-30 year fixed-interest mortgage and lives in it thriftily for the rest of their lives. The payments will seem high at the beginning. But by the end of the process, inflation and income growth will have reduced their importance in the family budget. By the time the mortgage is paid off, years ahead of time, it won't even be a very big bill in the general scheme of things. If at the same time, they reduce other bills, they might even make double payments on the mortgage.

And so, if the national-level process follows the established pattern since 1945, the deficit will be reduced to a manageable negative three to five percent within a few years here, perhaps sooner, while the debt itself will go away over a longer period of time, although never completely. The total debt level is in fact not that important once the correct deficit to GDP ratio is reestablished. And most of this will be achieved by the new tax hikes and spending cuts already in the pipeline, which don't really make a big difference to younger people at the beginning of their careers, unless they are already making large salaries.

Hence, by the way, Speaker of the House Beohner's recent confession on national TV that the palaver over the debt and deficit is just that, palaver.

None of this rational argument is going to make a big dint in the pessimism of a member of the younger generation who has fallen victim to the recent, mostly right-wing propaganda about the debt and deficit. I'm getting too long in the tooth to expect that propaganda goes away just because some professor proves it bull with a few statistics. The viral meme is just too strong. But I expect that the fuss will die down over the next few years, as fussing about the debt drops off the national radar a little at a time.

What was interesting about my Facebook exchange was that this particular alumnus's pessimism was compounded by the addition of climate change to his Calculus of Doom. This is of course not usually a concern for the right wing in US politics. But I can see how someone might be lured into seeing them as part and parcel of the same rigged scheme, youth versus age.

Essentially, in this view, the older generation is sticking the younger one with both a large un-payable debt and a deteriorating climate.

OK. Now there's one point there I can at least in part agree with. If we don't do something rational about climate change soon, we will have stuck the younger generation with a terrible burden.

But what's the solution? And what is the relationship of the solution to the federal debt and to Keynesian economics?

There are essentially two economic roads out of the climate crisis. One is to adopt a strong ecological economics prescription of low or zero growth, a Dalian steady-state economy.

The other is to grow a green energy economy, which would also grow GDP, to essentially continue on the current pathway of growth economics, only to replace dirty energy sources with green ones.

Certainly we're in trouble with the deficit if we adopt a zero growth plan. Without GDP growth, the deficit and debt will remain large in comparison to GDP, and would be very hard to pay off. A low or zero growth plan will also require unimaginably large programs of social reeducation (to reduce the power of consumerism) and a huge reevaluation of the idea of work in American society (the small amount of remaining work would have to be much more equally shared out) if it isn't going to look and feel like a horrible depression.

But we're almost certainly not going to choose this option anyway.

Particularly given the most recent political climate in the US, the same political climate that produced the deficit propaganda this former student is swallowing, I don't for a minute imagine that American society is ready to give up on growth economics and reevaluate consumerism and employment as foundations for society. That's just too much to ask.

This plan would also require an almost impossible level of public education regarding the dangers of climate change and other sustainability problems, as well as complete revision of the American mythology about capitalism. It just isn't very likely to happen anytime soon.

Even though I studied under Daly, and even though I think ecological economics is a great scientific improvement over neo-classical and even Keynesian economics, and even though I would like to see the world begin to move towards acceptance of the steady-state reasoning that you can't grow an economy forever on a finite planet, I understand that explaining this notion to the American people right now is going to be very, very difficult to do.

But I don't think that business-as-usual capitalism is a safe pathway, either. That will almost certainly result in the kind of damage ot the climate and to planetary ecosystems that this alumus is worried about.

What I think might succeed in the current political environment is a kind of green Keynesianism, whereby we learn to invest in renewable energy not just as the solution to climate change, but as a green economic stimulus. This has the added advantage of supporting global democracy. It's a lot better for the domestic economy and for global democracy if we spend our energy dollars internally on solar power and wind power and energy efficiency, than if we give those dollars to the world's various and multiple petrostate dictatorships.

But this plan might call for more, not less fiscal stimulus, especially if the economic model used required a lot of government intervention to set up the correct market conditions. It might even add to the deficit, at least in the short term.

If you put me in charge of the US government, I'd probably run up the deficit over several years to pay for some serious energy research and a lot of renewable energy and energy efficiency measures, all to prevent climate change!

I'd be careful not to run it up more than we could afford to pay for on the proceeds of the very large domestic energy and reconstruction boom we would then have.

But I'd run it up nevertheless.

Of course, this idea is a non-starter too, at least without a major change in US politics.

One other notion that received at least some bipartisan support a while back, even (for a very short while) from the irrepressible deficit scold himself, Grover Norquist, is that we might reduce climate emissions in a deficit-neutral manner by using a carbon tax to switch incentives around within the economy, to reduce the amount of government investment needed by using private money in response to market-based incentives.

Tax fossil fuels, subsidize renewables and efficiency.

You could, if you were really clever, even use the carbon tax to begin to pay down the debt.

Now there's a thought. Two birds with one stone.

Of course, thinking complex thoughts like this about the climate crisis and the American electorate requires a considerable amount of economic and political science education. And not just about ordinary or mainstream economics. Young people should be given the facts about climate change, as well as an education in these three competing economic models, and then even asked to evaluate a Dalian zero growth or steady-state model against this green Keynesian model.

We cover all this in our Unity College economics classes, and even in our required Core III Environmental Sustainability class.

I do believe, though, that my own sophistication about these ideas has probably grown since this particular student was in any of my classes.

I certainly I don't expect we'll get there on Facebook.

Friday, March 15, 2013

Bolivia, anyone?

Hello Mick,

Moscoso Architecture, a sustainable, organic architecture firm in Bolivia, is offering students a Sustainable Architecture Internship this Summer 2013. The details of the program are attached to this email. I know you circulated the opportunity last summer, so would it be possible to circulate this opportunity to your student body and/or post the listing on your careers/internship page for this year?

If you require more information about the program or organization, please do not hesitate to contact me or check out our website: www.moscosoarquitectura.com.bo

Moscoso Architecture, a sustainable, organic architecture firm in Bolivia, is offering students a Sustainable Architecture Internship this Summer 2013. The details of the program are attached to this email. I know you circulated the opportunity last summer, so would it be possible to circulate this opportunity to your student body and/or post the listing on your careers/internship page for this year?

If you require more information about the program or organization, please do not hesitate to contact me or check out our website: www.moscosoarquitectura.com.bo

Wednesday, March 13, 2013

The big plan

According to Andrew Revkin's New York Times environmental blog, a group of Stanford scientists and energy wonks have come up with a green energy plan for New York State, one which doesn't require nuclear power or natural gas.

I'll have to review this paper carefully, because if they have thought things through as they say they have thought things through, then they must either a) have new ideas and information on the problem of wind and solar power intermittency, or b) have skipped over this knotty problem altogether.

Always the realist-but-optimist, I'll hope for the former. I may even be able to find time to read the paper later today.

For his part, Revkin is, as always, quite skeptical.

This recommendation appears to be in a class of energy proposals we might call "All-in Green, ASAP."

These kinds of proposals, of which I've reviewed several now, including the seminal Zero Carbon Britain from the quite excellent Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales, require the reader to imagine a future where some reasonable, responsible state or federal government is willing to take very strong steps to encourage renewables and efficiency, along the way essentially forcing massive asset value reductions on owners of private property in fossil energy.

The value of coal deposits, fracking wells and other oil, gas, and coal infrastructure would be taxed or regulated away, creating, we should mention, a whole new class of political opponents of green policies.

(This reactionary class already exists, de facto. The Koch brothers lead it.)

I'm doubtful anything quite this extensive will actually happen. As I've mentioned elsewhere on this blog, while such strong steps might be economically and geophysically rational in the face of climate change, they are very difficult steps for the Anglo-American world to take, given our economic theology.

(I'm choosing the word theology carefully and correctly here -- we don't have a national economic theory in the USA or Britain. It's instead a theology, built more around myths and stories than around empirical evidence and analysis of that evidence.)

The Anglo-American version of society, or economic theology -- the one we get in the USA, Britain, Canada, Australia, and so on -- results in a combination of strong capitalism with weak social order and weak democracy.

The countries that have taken steps to enact an All-in Green energy model -- Germany, Sweden and Denmark are good examples -- have stronger democracies, stronger social order, and weaker capitalism. It's a lot easier for them to abolish value in private property.

This would be a good time to mention that an experiment with strong democracy and weaker capitalism did take place, once upon a time, in one Anglo-American country, the United Kingdom, from 1945 to 1979.

Britain's Welfare State, until it was mortally weakened by Margaret Thatcher, abolished massive quantities of private capital with some-but-minimal compensation using measures that were still legal and constitutional, such as the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, or the various acts that nationalized the British steel and coal industries, or established the National Health Service. The Labour Party architects of the Welfare State even attempted to spread this theory to the many colonies Britain still had at the time. It's hard to imagine the nationalized sugar industry developments in Belize (then British Honduras) or the infamous debacle of the African Groundnut Scheme, but these things existed, and probably should be studied by serious economists looking for ways to evaluate precedent in economic management for climate change.

All this was accompanied by a strong Fabian social order. There was a general scheme of leveling -- aristocrats and plutocrats alike were "soaked" in taxes until they declined in number and power -- or left for greener pastures. One result was the Fabianization of the countryside and the strong measures for countryside protection creating Britain's current very crowded cities and suburbs, while maintaining the green fields and patchwork farms (that I so love to hike over, when I return home).

Of course, Welfare State Britain was also uncompetitive and eventually fell behind in productivity and innovation. Much as I detested the Thatcher policies at the time, eventually they led to a more vibrant and more economically viable state.

Will climate change require an economic revolution in the USA, similar to that in Britain after World War Two?

Or will we find a way to continue with strong American capitalism and weak American democracy and social order, and still enact a serious climate-and-energy plan?

The jury is still out. But serious climate wonks will have to think it all through.

(Which, by the way, requires a very different education than we currently require for climate wonks.)

I'll have to review this paper carefully, because if they have thought things through as they say they have thought things through, then they must either a) have new ideas and information on the problem of wind and solar power intermittency, or b) have skipped over this knotty problem altogether.

Always the realist-but-optimist, I'll hope for the former. I may even be able to find time to read the paper later today.

For his part, Revkin is, as always, quite skeptical.

This recommendation appears to be in a class of energy proposals we might call "All-in Green, ASAP."

These kinds of proposals, of which I've reviewed several now, including the seminal Zero Carbon Britain from the quite excellent Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales, require the reader to imagine a future where some reasonable, responsible state or federal government is willing to take very strong steps to encourage renewables and efficiency, along the way essentially forcing massive asset value reductions on owners of private property in fossil energy.

The value of coal deposits, fracking wells and other oil, gas, and coal infrastructure would be taxed or regulated away, creating, we should mention, a whole new class of political opponents of green policies.

(This reactionary class already exists, de facto. The Koch brothers lead it.)

I'm doubtful anything quite this extensive will actually happen. As I've mentioned elsewhere on this blog, while such strong steps might be economically and geophysically rational in the face of climate change, they are very difficult steps for the Anglo-American world to take, given our economic theology.

(I'm choosing the word theology carefully and correctly here -- we don't have a national economic theory in the USA or Britain. It's instead a theology, built more around myths and stories than around empirical evidence and analysis of that evidence.)

The Anglo-American version of society, or economic theology -- the one we get in the USA, Britain, Canada, Australia, and so on -- results in a combination of strong capitalism with weak social order and weak democracy.

The countries that have taken steps to enact an All-in Green energy model -- Germany, Sweden and Denmark are good examples -- have stronger democracies, stronger social order, and weaker capitalism. It's a lot easier for them to abolish value in private property.

This would be a good time to mention that an experiment with strong democracy and weaker capitalism did take place, once upon a time, in one Anglo-American country, the United Kingdom, from 1945 to 1979.

Britain's Welfare State, until it was mortally weakened by Margaret Thatcher, abolished massive quantities of private capital with some-but-minimal compensation using measures that were still legal and constitutional, such as the 1947 Town and Country Planning Act, or the various acts that nationalized the British steel and coal industries, or established the National Health Service. The Labour Party architects of the Welfare State even attempted to spread this theory to the many colonies Britain still had at the time. It's hard to imagine the nationalized sugar industry developments in Belize (then British Honduras) or the infamous debacle of the African Groundnut Scheme, but these things existed, and probably should be studied by serious economists looking for ways to evaluate precedent in economic management for climate change.

All this was accompanied by a strong Fabian social order. There was a general scheme of leveling -- aristocrats and plutocrats alike were "soaked" in taxes until they declined in number and power -- or left for greener pastures. One result was the Fabianization of the countryside and the strong measures for countryside protection creating Britain's current very crowded cities and suburbs, while maintaining the green fields and patchwork farms (that I so love to hike over, when I return home).

Of course, Welfare State Britain was also uncompetitive and eventually fell behind in productivity and innovation. Much as I detested the Thatcher policies at the time, eventually they led to a more vibrant and more economically viable state.

Will climate change require an economic revolution in the USA, similar to that in Britain after World War Two?

Or will we find a way to continue with strong American capitalism and weak American democracy and social order, and still enact a serious climate-and-energy plan?

The jury is still out. But serious climate wonks will have to think it all through.

(Which, by the way, requires a very different education than we currently require for climate wonks.)

Monday, March 11, 2013

I know how she feels...

I know exactly how she feels.

There have been times, especially when trying to teach climate science to some of our more conservative "hook-and-bullet" traditional conservation majors, when I've felt exactly like this.

I may even have thrown chalk. Or bounced the blackboard eraser off the wall.

(Of course, it never did my student evaluations much good.)

Sunday, March 10, 2013

Taxonomy of the Latin-American left-wing

We were discussing Hugo Chavez's death in class the other day, and what importance Venezuelan oil production has for US foreign policy and for global climate change mitigation.

Here's an interesting perspective from the Guardian.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/mar/10/hugo-chavez-hector-abad-latin-america-left

Here's an interesting perspective from the Guardian.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/mar/10/hugo-chavez-hector-abad-latin-america-left

Saturday, March 9, 2013

Mauna Loa

We were just talking about this increased rate of change in class Thursday, and then this came out today.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/mar/08/hawaii-climate-change-second-greatest-annual-rise-emissions

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/mar/08/hawaii-climate-change-second-greatest-annual-rise-emissions

Friday, March 8, 2013

Pope on climate

And not the usual one (the one in charge of the Sierra Club), either. This one is a farmer called "Clay" and comes from Oklahoma.

The penny drops...

I'm tempted to say "duh".

New Report of the Australian Climate Commission, titled "The Angry Summer"

Key facts:

The important realization, and the one that will eventually take hold politically, is that climate change costs more money than energy efficiency and switching to renewable energy.

The question is, will that realization, combined with the long lead time required for the switch, happen soon enough?

New Report of the Australian Climate Commission, titled "The Angry Summer"

Key facts:

- The Australian summer over 2012 and 2013 has been defined by extreme weather events across much of the continent, including record-breaking heat, severe bushfires, extreme rainfall and damaging flooding. Extreme heatwaves and catastrophic bushfire conditions during the Angry Summer were made worse by climate change.

- All weather, including extreme weather events is influenced by climate change. All extreme weather events are now occurring in a climate system that is warmer and moister than it was 50 years ago. This influences the nature, impact and intensity of extreme weather events.

- Australia’s Angry Summer shows that climate change is already adversely affecting Australians. The significant impacts of extreme weather on people, property, communities and the environment highlight the serious consequences of failing to adequately address climate change.

- It is highly likely that extreme hot weather will become even more frequent and severe in Australia and around the globe, over the coming decades. The decisions we make this decade will largely determine the severity of climate change and its influence on extreme events for our grandchildren.

- It is critical that we are aware of the influence of climate change on many types of extreme weather so that communities, emergency services and governments prepare for the risk of increasingly severe and frequent extreme weather.

The important realization, and the one that will eventually take hold politically, is that climate change costs more money than energy efficiency and switching to renewable energy.

The question is, will that realization, combined with the long lead time required for the switch, happen soon enough?

Tuesday, March 5, 2013

Climate cabinet picks

If confirmed by the Senate, this will be the new Climate Cabinet.

It's not as radical as some would like. But then, no-one gets all of what they want, all of the time.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/05/us/politics/obama-names-2-to-fill-epa-and-energy-posts.html?hpw

It's not as radical as some would like. But then, no-one gets all of what they want, all of the time.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/05/us/politics/obama-names-2-to-fill-epa-and-energy-posts.html?hpw

Energy job suitable for SEM graduates

Energy Analyst

Job Description

TRC is seeking a qualified energy analyst to support commercial, institutional and residential energy efficiency and demand side management programs. Candidates must possess knowledge of building systems, energy efficiency, green building and sustainability. The energy analyst will work collaboratively with clients to develop market transforming programs that promote energy efficiency and demand side management technologies.

Key responsibilities include:

Required Skills

Position Type

Full-Time/Regular

Job Description

TRC is seeking a qualified energy analyst to support commercial, institutional and residential energy efficiency and demand side management programs. Candidates must possess knowledge of building systems, energy efficiency, green building and sustainability. The energy analyst will work collaboratively with clients to develop market transforming programs that promote energy efficiency and demand side management technologies.

Key responsibilities include:

- Develop with senior level assistance technical standards, protocols and requirements for innovative energy efficiency and demand side management programs;

- Perform and review facility energy audits, feasibility studies and reports;

- Develop and implement with senior level assistance quality assurance procedures for energy and green building programs;

- Research emerging technologies and standards;

- Review calculations and assumptions used to estimate or measure savings due to energy efficiency or green projects;

- Conduct site visits to verify installation and operation of technologies;

- Communicate with contractors and program participants regarding program rules and requirements;

- Utilize energy modeling applications and spreadsheets to compare projected energy savings to actual.

Required Skills

- Bachelors or Masters degree in Engineering; Architecture, Planning, Environmental Science, Natural Resource Management or Economics;

- Knowledge of building systems, energy efficiency technologies, green building and high performance design;

- Knowledge of energy efficiency or green building or related environmental / resource management programs is a strong plus;

- Understanding of marketing strategy and market analysis techniques is a strong plus;

- Excellent oral and written communications skills;

- Team-oriented, hands-on, highly skilled, adaptive, and client-focused;

- Required Experience

- Academic and / or professional experience displaying a strong interest in sustainability, green building or energy efficiency.

- 1-5 years of experience within the green building, energy efficiency, building industry, environmental or resource management is preferred;

- Experience with modeling techniques related to energy or environmental planning is a strong plus;

- Job Location

Position Type

Full-Time/Regular

Sunday, March 3, 2013

Eeeek-lectricity

We did some of the classic experiments in electrostatics, electric current generation, and associated phenomena in Physics II Laboratory Friday.

First, students made crystal radios using small kits. The kits weren't very good, and students struggled with the instructions and some of the fiddly processes. But once we had one or two working, we set them aside and switched to other experiments, then combined the two.

We then ran the Van der Graaff generator through its paces, using it to visualize first electrostatic discharge (sparks, seen above), then to light a CFL light bulb, then, with the aid of some aluminum pie plates and soap bubbles, charge transfer.

(The VdG can light a florescent bulb, the pie plates, placed on top of the sphere, fly off the VdG, one by one, as they accumulate charge, and the soap bubbles are initially attracted to the VdG then repelled violently.)

Here are students fiddling with their radios' electronics:

And here, of course, is the classic VDG genny charge transfer experiment: find the student with the longest driest hair, stand him on an insulator (an old milk crate), and charge him up until he crackles and his hair sticks straight up.

Samuel was, I must say, perfect for purpose.

(Thanks, Sam, for contributing your excellent hair and sense of humor to science.)

Then, we pulled out a hand-held Tesla coil and used it to visualize electric current transfer using sparks and an old light bulb.

Finally, we transmitted Morse signals to the crystal radios using bursts of Tesla coil energy (because spark transfer makes Hertzian waves), essentially replicating the early http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guglielmo_Marconi-type spark transfer radios.

Here are some You Tube videos showing similar experiments:

Materials on fracking for class

An article about fracking in Poland:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/mar/01/frontline-poland-fracking-frontier

The clip from GasLand we watched in class.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phCibwj396I

And the Cato Institute interview of Phelim McAleer, about Frack Nation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11Ngrd-Opd0

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2013/mar/01/frontline-poland-fracking-frontier

The clip from GasLand we watched in class.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=phCibwj396I

And the Cato Institute interview of Phelim McAleer, about Frack Nation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=11Ngrd-Opd0

Guardian student bloggers

I was looking for articles on distance learning for a committee I'm chairing, when I stumbled across the Guardian's UK student blog.

Some of the posts are, of course, trivial, but others are interesting and give insight into the life of students at university in the UK.

It's particularly interesting to me because, although I'm British and completed high school and technical college in Britain, my university education is entirely American. This is partly because of the class system in the UK. I was born into a very solidly working class Sheffield family that had never sent yet one of its children to university until my sister and I broke the mold. When class is not just about income but also about culture and tribe, and class barriers are rigidly enforced (on both sides of the divide), this kind of thing can easily happen, and still does happen in Britain.

I still needed to delve into distance learning for my committee, so I read the comments on a student-written blog article about MOOCs.

One note I read mentioned a reason for British students to study American MOOCs:

"...American lecturers have no middle class agenda and talk to an audience they assume find it difficult so try to explain clearly whereas most Britsih lecturers try to make things more complicated than they are to keep out the rif raff."

So, in other words, this students believes that snotty middle-class professors ("lecturers" in British) at UK institutions don't like to come down to the level where their students are at.

There's a problem with this if the students aren't doing the work. If you don't make an effort to keep up in one of my classes, you will be left behind, and although I'll try to help you catch up, I won't be happy about it.

But if the author is right (based on my own experiences I think he is, at least partly), then one consequence of the postwar nationalization of UK higher education, still in force, more or less, has been that professors believe, perhaps subconsciously, they can still get away with this kind of thing.

BTW, it's not too late to do the Unity College Distance Learning Survey.

Do it. Do it now.

Some of the posts are, of course, trivial, but others are interesting and give insight into the life of students at university in the UK.

It's particularly interesting to me because, although I'm British and completed high school and technical college in Britain, my university education is entirely American. This is partly because of the class system in the UK. I was born into a very solidly working class Sheffield family that had never sent yet one of its children to university until my sister and I broke the mold. When class is not just about income but also about culture and tribe, and class barriers are rigidly enforced (on both sides of the divide), this kind of thing can easily happen, and still does happen in Britain.

I still needed to delve into distance learning for my committee, so I read the comments on a student-written blog article about MOOCs.

One note I read mentioned a reason for British students to study American MOOCs:

"...American lecturers have no middle class agenda and talk to an audience they assume find it difficult so try to explain clearly whereas most Britsih lecturers try to make things more complicated than they are to keep out the rif raff."

So, in other words, this students believes that snotty middle-class professors ("lecturers" in British) at UK institutions don't like to come down to the level where their students are at.

There's a problem with this if the students aren't doing the work. If you don't make an effort to keep up in one of my classes, you will be left behind, and although I'll try to help you catch up, I won't be happy about it.

But if the author is right (based on my own experiences I think he is, at least partly), then one consequence of the postwar nationalization of UK higher education, still in force, more or less, has been that professors believe, perhaps subconsciously, they can still get away with this kind of thing.

BTW, it's not too late to do the Unity College Distance Learning Survey.

Do it. Do it now.

Saturday, March 2, 2013

Simms solutions?

Andrew Simms, an important progressive economist in Britain, has a new book about climate economics, called Cancel the Apocalypse: the New Path to Prosperity

This is a welcome addition to the climate debate.

I have to say, I've been very disappointed by the lack of economic literacy and common sense in several of the prescriptions I've read from environmentalists recently, even quite famous and important ones, so I'm looking forward to reading Simms's book.

Simms is a Keynesian with training in ecological economics, which, regular readers will know, is what I think is the correct approach, or mix of approaches. There are very few folks in the economics profession who have this background.

Most ecological economists and quite a lot of climate campaigners want to abolish a good deal of private property and make a fair chunk of normal capitalistic activity illegal. They may not quite realize they want to do this, but this is the natural consequence of some of their prescriptions.

They need to think it through some more.

Here's an example. Suppose we came up with a policy prohibiting the use of coal in the US, desirable from a climate point of view? This would essentially abolish the value of a large amount of private property in US coal. It would also cause difficulty for industrial processes that use coal as in input in production, such as the steel industry.

Or a policy banning the use of tar sands in the US, again quite sensible from a climate point of view?

Is oil from Canadian tar sands as nasty a product as, say, illegal drugs from Canada? Probably, considering the climate damage, but it's very hard for the US to completely ban it, given current rules and regulations and the primacy of capitalism in general in both the US and Canada. What if the tar sands have already been refined and are essentially indistinguishable from ordinary oil products such as gasoline? Can they still not be imported? This would mean that every "Irving" oil truck (a Canadian brand with many outlets in Maine) that crosses the border would have to have chemical analysis to performed on the contents.

You see the difficulty.

I tend to think that taking steps like these might be reasonable and even desirable, but are unrealistic in today's political economy. Public opinion in the west, especially the US, Britain, Australia and Canada -- the countries with the strongest version of free market economics -- is not even close to taking steps this radical.

Even though I'm quite willing to admit that taking such radical steps might be reasonable, given the climate consequences, I don't think they are politically feasible.

I tend to think we will do better, faster, if we choose to work with the list of typical Keynesian measures: taxes, subsidies, encouragements to invest, and fiscal stimulus, but all targeted carefully to promote renewable energy and energy efficiency, and, of course, targeted carefully against high-carbon energy sources. Then we don't have to take on capitalism and climate change at the same time. We can use capitalism as an ally in the battle against climate change, not make it an enemy, as we seem to be trying to do now.

So I'm looking forward to reading Simms' book. In his article for the Guardian, linked above, Simms even cites Keynes' most important work (in my opinion), the short pamphlett How to Pay for the War.

It's coming from the UK, so it will be a while. But I'll let you know.

This is a welcome addition to the climate debate.

I have to say, I've been very disappointed by the lack of economic literacy and common sense in several of the prescriptions I've read from environmentalists recently, even quite famous and important ones, so I'm looking forward to reading Simms's book.

Simms is a Keynesian with training in ecological economics, which, regular readers will know, is what I think is the correct approach, or mix of approaches. There are very few folks in the economics profession who have this background.

Most ecological economists and quite a lot of climate campaigners want to abolish a good deal of private property and make a fair chunk of normal capitalistic activity illegal. They may not quite realize they want to do this, but this is the natural consequence of some of their prescriptions.

They need to think it through some more.

Here's an example. Suppose we came up with a policy prohibiting the use of coal in the US, desirable from a climate point of view? This would essentially abolish the value of a large amount of private property in US coal. It would also cause difficulty for industrial processes that use coal as in input in production, such as the steel industry.

Or a policy banning the use of tar sands in the US, again quite sensible from a climate point of view?

Is oil from Canadian tar sands as nasty a product as, say, illegal drugs from Canada? Probably, considering the climate damage, but it's very hard for the US to completely ban it, given current rules and regulations and the primacy of capitalism in general in both the US and Canada. What if the tar sands have already been refined and are essentially indistinguishable from ordinary oil products such as gasoline? Can they still not be imported? This would mean that every "Irving" oil truck (a Canadian brand with many outlets in Maine) that crosses the border would have to have chemical analysis to performed on the contents.

You see the difficulty.

I tend to think that taking steps like these might be reasonable and even desirable, but are unrealistic in today's political economy. Public opinion in the west, especially the US, Britain, Australia and Canada -- the countries with the strongest version of free market economics -- is not even close to taking steps this radical.

Even though I'm quite willing to admit that taking such radical steps might be reasonable, given the climate consequences, I don't think they are politically feasible.

I tend to think we will do better, faster, if we choose to work with the list of typical Keynesian measures: taxes, subsidies, encouragements to invest, and fiscal stimulus, but all targeted carefully to promote renewable energy and energy efficiency, and, of course, targeted carefully against high-carbon energy sources. Then we don't have to take on capitalism and climate change at the same time. We can use capitalism as an ally in the battle against climate change, not make it an enemy, as we seem to be trying to do now.

So I'm looking forward to reading Simms' book. In his article for the Guardian, linked above, Simms even cites Keynes' most important work (in my opinion), the short pamphlett How to Pay for the War.

It's coming from the UK, so it will be a while. But I'll let you know.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)