- Fill out the Home Energy Saver at http://homeenergysaver.lbl.gov/consumer/ and hand in the main report page (the one with the histogram of results), also with a short report detailing your results and a paragraph of reflection on the results, or

- Complete the modeling homework assignment. You will most likely need to see me to get some coaching in using Excel or a dynamic systems software package for this type of model.

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Core III final homework assignment

Either:

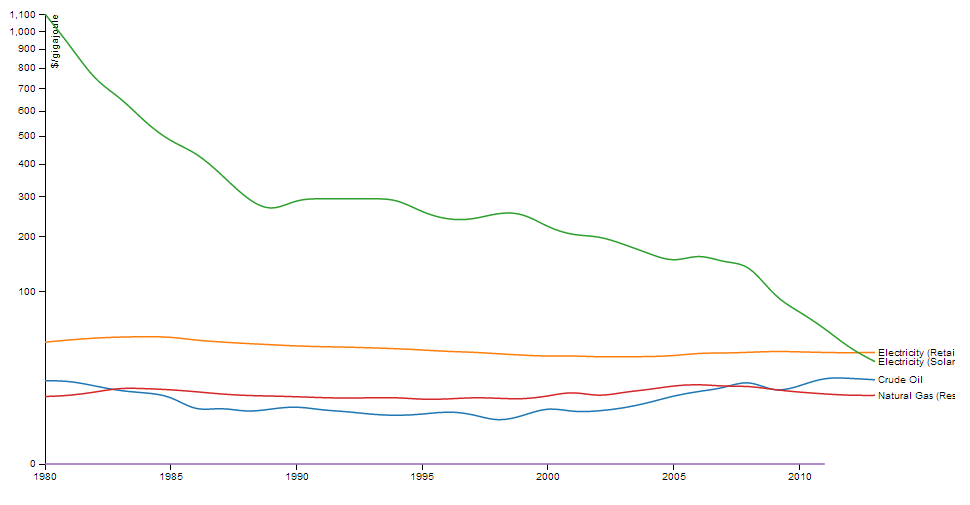

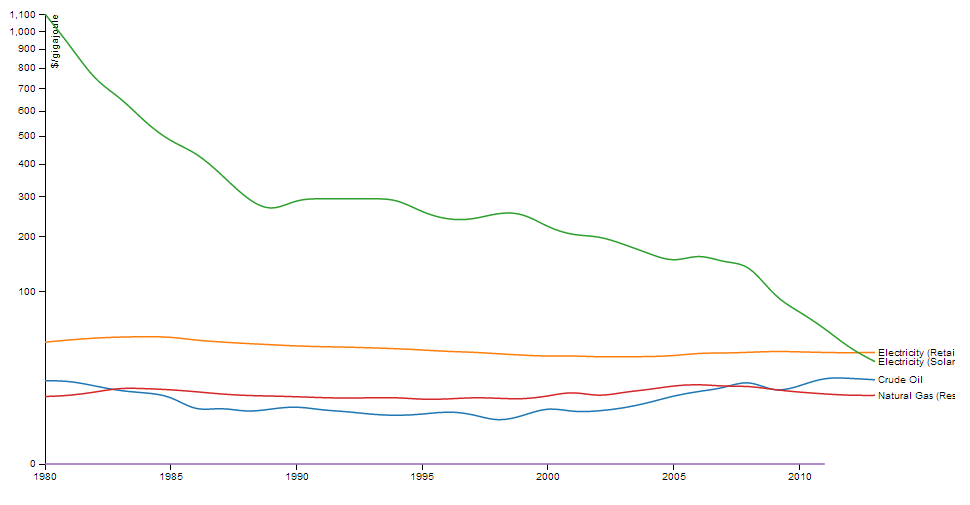

Disruptive: Is solar PV now cheaper than coal?

Here are images from two very different news outlets, "chalk and cheese" as we say in the UK, but with the same message. Solar PV may now be cheaper than coal even without taking negative externalities into account.

The first is from Brian McConnell, published in the alternative energy blog Resilience. Click to enlarge.

The second is from the much more conservative Economist.

The first is from Brian McConnell, published in the alternative energy blog Resilience. Click to enlarge.

The second is from the much more conservative Economist.

Monday, April 29, 2013

Kempton on electric car/grid stability nexus in NYT

I was pleased to find one of my PhD thesis advisors, Willett Kempton of UDel, in my morning paper today, talking about using electric cars for grid stability.

A previous article, a few days back, was about using cars to provide power to overcome intermittency.

This article is about using cars to maintain 60 cycle frequency.

A previous article, a few days back, was about using cars to provide power to overcome intermittency.

This article is about using cars to maintain 60 cycle frequency.

Sunday, April 28, 2013

Optimistic

Students tired of the doomsday beat and looking for optimistic viewpoints to try on for size (for their final essay in Core III) might like this one, from Andrew Revkin's New York Times Blog:

http://dotearth.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/27/an-earth-scientist-explores-the-biggest-climate-threat-fear/#more-49188

And, actually (thirty minutes later into my Sunday papers), here's another:

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/25/business/energy-environment/by-2023-a-changed-world-in-energy.html?pagewanted=1&src=recg

A word of caution: Both optimism and pessimism are addictive.

http://dotearth.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/04/27/an-earth-scientist-explores-the-biggest-climate-threat-fear/#more-49188

And, actually (thirty minutes later into my Sunday papers), here's another:

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/25/business/energy-environment/by-2023-a-changed-world-in-energy.html?pagewanted=1&src=recg

A word of caution: Both optimism and pessimism are addictive.

Saturday, April 27, 2013

Can human civilization become ecologically sustainable?

That would be the final essay question in our Core III General Education class, Environmental Sustainability, currently being offered for the last time. We've been teaching this class since Fall Semester 2000.

We ? Me, actually. Mostly me.

I've been teaching this class since then without a break, every semester of every year.

I expect I've taught over 85% of the total sections offered over the years. Some years, I've taught as many as five sections. It was, as I said in an essay in 2004, "Preaching NOT to the converted."

Most Unity College students did not want to take the class, all were forced to take it by the college's system, and the great majority, at least to begin each semester, acted accordingly. They sulked, they pouted, they drug their heels, they didn't do the work, they didn't come to class, and some of them, usually about 25% on the first midterm, flunked the exams.

Yet most, after what was often extreme efforts at communication on both our parts, ended the class with at least a starting appreciation of the difficulties humanity faces. By the time they finished, well over 98% had passing grades.

Part of the reason for this is simply that I'm extremely stubborn. (Once a Yorkshireman, always a Yorkshireman.) So I would never take "no" for an answer. Students who didn't want to do the assignments, who didn't want to think, were generally made to, through fair means or foul. My teaching evaluations reflect this. I can look back in humor now, but there were always a handful of recalcitrant students, one or two percent, who, on learning that they wouldn't graduate before handing in some assignment or another, would write "fire Mick" on their evaluations!

But Core III was a core class. You are not allowed to graduate before you get a passing grade in all your core classes. The professor in each core class therefore has a veto on your graduation. I used that authority to the hilt to make students do the work.

I think I would do the same again, if put in the same position.

It just doesn't seem right to me, that a person offered the opportunity to review scientific and balanced information about the future of humanity, would want to ignore that information. To want to do so fails the first test of intellectual curiosity. It shows that you're simply not a scholar of any dimension.

And so I never allowed it.

As always when any great period in a person's life comes to an end there will be a reflective reckoning. I long ago discovered that the key to mental health and the key to being a good academic was internal reflection.

I'll let you know how I feel about the end of Core III as soon as I know what I feel. But I do know that if I come to the end of my life having done nothing further for the planet, teaching what was probably about 52 sections of this course to an average of 20 or so students a section, making some 1000 students in all, was at least a modestly serious contribution. And some great planetary warriors and thinkers have come through this class over the years.

No need to name names. You know who you are.

Here's an interesting article to help the current students with their final essay.

The final, final essay.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/blog/ecological-challenge-too-late-sustainability

We ? Me, actually. Mostly me.

I've been teaching this class since then without a break, every semester of every year.

I expect I've taught over 85% of the total sections offered over the years. Some years, I've taught as many as five sections. It was, as I said in an essay in 2004, "Preaching NOT to the converted."

Most Unity College students did not want to take the class, all were forced to take it by the college's system, and the great majority, at least to begin each semester, acted accordingly. They sulked, they pouted, they drug their heels, they didn't do the work, they didn't come to class, and some of them, usually about 25% on the first midterm, flunked the exams.

Yet most, after what was often extreme efforts at communication on both our parts, ended the class with at least a starting appreciation of the difficulties humanity faces. By the time they finished, well over 98% had passing grades.

Part of the reason for this is simply that I'm extremely stubborn. (Once a Yorkshireman, always a Yorkshireman.) So I would never take "no" for an answer. Students who didn't want to do the assignments, who didn't want to think, were generally made to, through fair means or foul. My teaching evaluations reflect this. I can look back in humor now, but there were always a handful of recalcitrant students, one or two percent, who, on learning that they wouldn't graduate before handing in some assignment or another, would write "fire Mick" on their evaluations!

But Core III was a core class. You are not allowed to graduate before you get a passing grade in all your core classes. The professor in each core class therefore has a veto on your graduation. I used that authority to the hilt to make students do the work.

I think I would do the same again, if put in the same position.

It just doesn't seem right to me, that a person offered the opportunity to review scientific and balanced information about the future of humanity, would want to ignore that information. To want to do so fails the first test of intellectual curiosity. It shows that you're simply not a scholar of any dimension.

And so I never allowed it.

As always when any great period in a person's life comes to an end there will be a reflective reckoning. I long ago discovered that the key to mental health and the key to being a good academic was internal reflection.

I'll let you know how I feel about the end of Core III as soon as I know what I feel. But I do know that if I come to the end of my life having done nothing further for the planet, teaching what was probably about 52 sections of this course to an average of 20 or so students a section, making some 1000 students in all, was at least a modestly serious contribution. And some great planetary warriors and thinkers have come through this class over the years.

No need to name names. You know who you are.

Here's an interesting article to help the current students with their final essay.

The final, final essay.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/sustainable-business/blog/ecological-challenge-too-late-sustainability

Industrial countries' emissions data

Mostly because I wanted to see if the embedded features would still work in Google. But it's good data to have handy.

Friday, April 26, 2013

Naming and shaming

Elsewhere on this blog over the years I've opined that one day there may become a tremendous reckoning for the purveyors of climate denial. Given that people are already losing their homes and being injured or dying to the additional or more intense extreme weather events we're already getting, and given the massive financial impact on ordinary people and businesses such as insurance that are exposed to massive losses, and given that matters are already worse than they need to be, due to the corruption and intransigence of denialist funders like the Koch brothers, or denialist political leaders like Senator Inhofe of Oklahoma, it's not unreasonable to imagine a future public so outraged by what has happened that new laws are passed, or methods found using old laws, to throw the bums in jail.

The best comparison seems to me to be with those isolationists and appeasers who thought that Adolf Hitler was just another German patriot we could do business with.

This day is not yet upon us, but at least the Obama political machine is trying to get the message out. See the new video below.

Ordinarily I don't post party political material on this blog, but to me this is no longer political.

It's a conflict of reason and science against corruption and bigotry.

The best comparison seems to me to be with those isolationists and appeasers who thought that Adolf Hitler was just another German patriot we could do business with.

This day is not yet upon us, but at least the Obama political machine is trying to get the message out. See the new video below.

Ordinarily I don't post party political material on this blog, but to me this is no longer political.

It's a conflict of reason and science against corruption and bigotry.

Thursday, April 25, 2013

Use electric cars for grid stability -- a truly great idea

We're in the part of Core III (Environmental Sustainability) where, every semester for a dozen years now, we talk about energy efficiency, renewable energy, and improved forms of conventional energy -- the mitigation response to climate change (when combined with methane and NOX abatement).

This requires that your humble professor maintain currency in the fast-moving world of energy systems. One area of importance is grid storage and systems to handle the inherent intermittency of solar, wind, and other renewable energy.

This new idea is to use smart grid charging of electric vehicles to round out peaks and valleys in the electric dispatch cycle.

Rocky Mountain Institute has for years suggested that the national electric car fleet would be useful as grid storage. This notion, from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, takes that idea a step further.

I can't say enough nice things about the role of the National Labs in energy science. They've really come through with some cool ideas in recent years.

Ordinarily, were we all suddenly to switch on our electric loads together, as, say, on Superbowl Sunday, grid-service organizations like ISO New England would normally call for spot-price dispatch.

Although not particularly polluting, this is the most expensive form of electricity. It generally comes from fast-dispatch natural gas turbine plants or grid-storage hydropower plants, and is used to power up the grid to handle peaks.

But instead, according to this idea, battery-charging loads from electric cars could be controlled remotely to round out peaks and troughs.

What a great idea!

In particular this would free up grid capacity to allow faster deployment and greater grid penetration of wind and solar power than would otherwise be possible.

Unfortunately, it could also be used to round out peaks and troughs that result from the use of inflexible coal thermal plants (which can't respond to demand spikes).

I subscribe to the optimistic view that coal is the "walking dead" or "zombie" form of electricity production, given the new lower price of gas, large scale wind and (distributed) solar, and given the more aggressive GHG regulation begun under the Obama EPA after Massachusetts vs. EPA, so I doubt any self-respecting grid operator would imagine they could expand the use of coal on this basis, at least in the US.

(Increased US exports of coal are another matter altogether, and will have to be dealt with ASAP, by some other means.)

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/25/business/energy-environment/preparing-for-the-power-demands-of-an-electric-car-boom.html?src=recg

This requires that your humble professor maintain currency in the fast-moving world of energy systems. One area of importance is grid storage and systems to handle the inherent intermittency of solar, wind, and other renewable energy.

This new idea is to use smart grid charging of electric vehicles to round out peaks and valleys in the electric dispatch cycle.

Rocky Mountain Institute has for years suggested that the national electric car fleet would be useful as grid storage. This notion, from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, takes that idea a step further.

I can't say enough nice things about the role of the National Labs in energy science. They've really come through with some cool ideas in recent years.

Ordinarily, were we all suddenly to switch on our electric loads together, as, say, on Superbowl Sunday, grid-service organizations like ISO New England would normally call for spot-price dispatch.

Although not particularly polluting, this is the most expensive form of electricity. It generally comes from fast-dispatch natural gas turbine plants or grid-storage hydropower plants, and is used to power up the grid to handle peaks.

But instead, according to this idea, battery-charging loads from electric cars could be controlled remotely to round out peaks and troughs.

What a great idea!

In particular this would free up grid capacity to allow faster deployment and greater grid penetration of wind and solar power than would otherwise be possible.

Unfortunately, it could also be used to round out peaks and troughs that result from the use of inflexible coal thermal plants (which can't respond to demand spikes).

I subscribe to the optimistic view that coal is the "walking dead" or "zombie" form of electricity production, given the new lower price of gas, large scale wind and (distributed) solar, and given the more aggressive GHG regulation begun under the Obama EPA after Massachusetts vs. EPA, so I doubt any self-respecting grid operator would imagine they could expand the use of coal on this basis, at least in the US.

(Increased US exports of coal are another matter altogether, and will have to be dealt with ASAP, by some other means.)

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/25/business/energy-environment/preparing-for-the-power-demands-of-an-electric-car-boom.html?src=recg

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

Divestment 2.0

This post is going to be a running list of ideas for individuals and families, institutions, and societies, to make further steps to wean themselves off fossil fuel. We're going to assume that the individuals and institutions have already done "Divestment 1.0," i.e., taken any financial assets out of fossil fuel using one or another reasonable, well-planned means.

(Actually, there are good economic reasons to believe that some items on this list should take priority over purely financial divestment. But it's silly to quibble over which step to take first, if both are in the right direction. When you go for a walk, do you start with the left or right leg?)

This is just the beginning. We'll add to the list as we go, and keep a link in the Sustainability Thought and Deed Annex, so we can find it easily.

For individuals and families:

For institutions:

For communities and societies:

(Actually, there are good economic reasons to believe that some items on this list should take priority over purely financial divestment. But it's silly to quibble over which step to take first, if both are in the right direction. When you go for a walk, do you start with the left or right leg?)

This is just the beginning. We'll add to the list as we go, and keep a link in the Sustainability Thought and Deed Annex, so we can find it easily.

For individuals and families:

- Get an energy audit. Weatherize and insulate your home, and replace oil heat systems with biofuels or renewably-generated electricity. Of the biofuels, firewood or pellet from sustainably managed, biodiverse forests or agro-forest ecosystems is probably best. In most cases this work will pay for itself. Growing or getting your own fuel, if you live in the country, is generally healthful

- Replace energy-inefficient appliances with energy-efficient ones. In most cases this work will pay for itself

- Walk or bike to work, or use public transport. In most cases this will pay for itself in terms of better physical health

- Either replace energy inefficient vehicles with energy efficient ones, or better yet, switch from gas/diesel to electric or hybrid electric ones running on renewable electricity. Use lifecycle analysis if you know how to do this. In some cases, running a less-efficient vehicle for a small number of miles a year for a specialized operation (eg: trucking hay or firewood), while using a fuel-efficient or electric vehicle for daily commuting, is a good combination.

- Either a) begin growing your own food in a garden or backyard livestock operation (there are interesting ecological combinations of the two, for instance, the Womerlippis use agro-forestry, gardening, and livestock together, combining waste streams from one operation into the nutrient cycle of the other), or b) begin to participate in your local food network, or some combination. In either case any extra manual work or expense will often pay for itself in terms of physical health

- Reconsider your vacation and other non-work related traveling to reduce fossil fuel needs

- Either a), give up your job in a fossil fuel-dependent industry or sector, and find a job in a fossil-free industry or sector, or at least move from an fossil-intensive sector to a less intensive one, or b), begin a sustainability program at your job.

- If your workplace or job makes it difficult for individuals or families to do things like the suggestions in 1 through 5 above, then campaign to make it otherwise, or try a different job

For institutions:

- Start a sustainability committee. If expertise is needed, hire it. Hire a sustainability coordinator

- Get deep energy audits of all operational functions. Use lifecycle thinking where appropriate

- Make a fully-costed priority list, with payback estimates, of energy-efficiency measures. Implement the list in a reasoned, planned manner. (Plugging away at a well-planned list over a long period is infinitely preferable, an generally much more successful than bipolar "trance and shock" approach.)

- Reconsider work travel. Is your journey really necessary? Make better use of webinars and Skype

- Don't forget easy to overlook sub-operations like the food service (local food!) or the motor pool

- Help your employees divest: Provide a fuel-efficient transport service. Organize a car pool, or day-care. Consider green employee housing, or free at-work charging stations for electric cars

- Invest institutional savings in cost-effective improvements

- Join professional and service organizations that will help you do all this, e.g, AASHE or the Billion Dollar Green Challenge

- If it isn't possible for the business or organization to do any part of what it does without fossil fuel, consider whether you should be doing it at all

For communities and societies:

- Review your economic development, planning and energy policies. Reconsider energy use and energy efficiency retrofit assistance in light of green Keynesian multipliers

- Take steps to reinforce local, regional and national multipliers using local, regional or domestic renewable energy and energy efficiency. Stop sending money out of the community to pay for fossil energy

- Reconsider society-wide economic incentives and disincentives. For instance, adopt cap and trade, or a Pigouvian tax on fossil fuel

- Encourage downsizing or lower impact lifestyles where possible. Not every person in society needs to be fully productive in the industrial economy. We may already have more production than we need, and in any case the development of labor-saving robotic machinery makes full employment much more difficult to achieve. In the absence of policies to encourage downsizing (a shorter working week, for instance, or a national wage) the benefits of improved production tend to go primarily to the already-wealthy

- Encourage cooperation over competition. Consider better incentives and policies for worker ownership, cooperatives, and community non-profit organizations

- Don't enact bans on backyard gardens and livestock such as chickens, on solar panels, wind turbines, on self-help building, and other desiderata, and prevent community associations and gated communities from doing the same

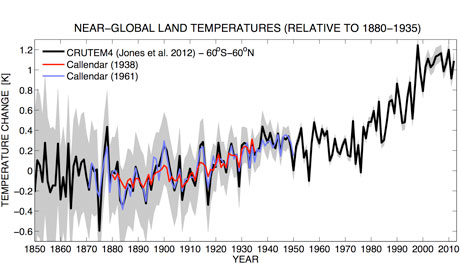

Callendar

Students in GL 4003 Global Change have not had much chance to discuss Callender's original 1938 paper on the role of carbon dioxide in global warming, although it was assigned and given out as part of the course "packet," along with Arrhenius' and Tyndall's earlier work. Here's your chance to put it in context.

Now a celebratory retrospective has appeared, for the 75th anniversary. It's well worth a few moments of time for anyone who's serious about understanding climate science.

Here's the Guardian article.

Here's the paper (in the RMS Quarterly).

Here's the data, comparing the original with the (much newer) HADcru4.

Pretty good for a (so-called) amateur, I'd say.

Sunday, April 21, 2013

Conference time!

Speaking at College of the Atlantic's conference on "Cooperation, Community and Complexity" later today. The conference is sponsored by the new American office of nef, one of my favorite think tanks, and I'm very pleased to be asked to speak.

My topic,

"Which economic theory will actually work to stop global climate change?"

http://coa.edu/ecocon

My starting thesis is that we don't actually properly practice any economic theory at all -- what we finish up with for economic policy in American and most western countries is a mish-mash of superstition, alarmism, bigotry, and factionalism, with a little self-serving theorizing, hand waving at Adam Smith or John Maynard Keynes, mixed in.

This is as true for American Democrats as it is for American Republicans, and indeed for most western nation political parties. It's also true for American environmentalists.

If we were rational we'd sit down and think it all out, eventually adopting ecological economics or something like that.

("Eco-eco" is the closest humanity has come to a scientifically literate economics. I'm proud to be one of its early adopters.)

But we're not going to do that, not just yet, anyway. Look around. Other than the afore-mentioned superstition, alarmism, bigotry, and factionalism, many Americans still think economics began and ended with Adam Smith, possibly crediting Milton Friedman for a few apocrypha. That portion of the remainder who cares probably assumes that progressive economics, such as that of the Obama administration, is "good enough for government work," and would simply like to see more of it. The rest just don't care. They're distracted by kittens on YouTube, or the War on Terror, or TV, or other drugs, legal and illegal, or, bless 'em, by just trying to make a living (just to name a few of the more common distractions we economics teachers encounter).

So we're heading into disruptive, dangerous climate change with both politics and economics, not to mention levels of public science education, that are wholly inadequate to the problem.

And, when you consider the climate change problem in this light, you begin to realize we don't have time to do much better. We have only another ten or twenty or perhaps thirty years here, in which we either have to eliminate more than 80 percent of current fossil fuel use, or find a cost-effective way to sequester an extra gigaton or two of carbon from the atmosphere each year, or do some combination, to avoid potentially clvilization-destroying climate change.

But we live in a democracy, and presumably value that fact.

So our distracted friends and neighbors, the folks with the wholly inadequate economics and politics, well they have a right to be distracted and to be climate-illiterate.

Oy.

This is a right that may kill the planet, but we can't deny them that right without repealing the Enlightenment, the sacrifices of two world wars and a cold one, and the hundreds of years of social evolution and sacrifice that went into developing democracy itself.

Oy vey.

What to do?

(That's my outline. I do have an answer to this question, but no spoilers!)

The farm life -- in college!

Lambing continues on our small farm and part-time agricultural science demonstration center. A three-year old Womerlippi farm ewe named Quetzal had given birth to two lambs when I came home from work on Thursday. I think it was Thursday. It's been a bit of a blur, this lambing season. Both were ewe-lambs, making a total of seven out of eight females.

The one boy, part of the first set of twins born on the farm this year, reminds me of a guy I once knew when I was in the British military. This airman, a London Irishman, had six older sisters who all liked to play "mother." This was in the 1960s and 1970s, so gender stereotypes were still powerful norms. He'd been the subject of so much attention as a kid, he could barely look after himself.

It's going to be an interesting experiment in nature versus nurture to see whether the lone ram actually expresses male behavioral traits or not, on time, as he normally would, considering how much female influence he has around him. My bet is on nature. I expect we'll see him begin to "ram" his sisters around within a few weeks here.

We now have only one remaining mother yet to give birth, a two-year old named Regina. She isn't terribly large, so it's probably a singleton, and I'm expecting a hard time for her since this is her first. Night checks are still needed, as well as regular visits to the paddock during the day, all to check that the lambs remain safe from bad dogs and coyotes, and that the last mother has not gone into labor.

The requirement to visit in the middle of the day remains the hardest part of being both a part-time shepherd and a full-time college professor. You essentially spend your lunch break driving home for a quick look-around, then driving back to work. It's a lot easier when one or the other of us is free to work from home. Then you can just put down your grading or reading or whatever it is that you're doing, and pop out the back door for a look-see, a nice break from work.

This year we messed up on timing. Pre-registration period, when students need their academic advisors to meet with them and choose classes and talk about careers and graduate school and wotnot, coincided with lambing. This was an artifact of other college work, particularly our accreditation review. With our professional personas up to our professional armpits in both advising and the (successful!) re-accreditation campaign, as well as admissions events and and the academic hiring season, shepherding time was hard to come by for the Womerlippis.

We should try to "get real" here.

In a "real" world, or at least in my ideal academic world, my colleagues and the college would see the true value of lambing season (and other experiential education opportunities) to sustainability studies and find ways for the students to cut classes too so they could see the shepherding process up close and personal.

Then they'd learn some applied mammalogy!

Students could then be there for the whole birthing process, learning at least some of the formal and instinctive midwifery required of every livestock farmer. In an ideal world, they'd even learn to warm cold lambs and to intubate. This kind of experience is really hard to come by, and vital to the commercial success of a sustainable farm.

But the fifty-minute class schedule, the secret ogre of college life, the "anti-education schedule", intervenes, every time, with such things, as to a lessor extent does the regular round of administrivial work.

The fifty-minute class norm, to my mind, is the greatest failure of critical thinking in American education today.

At our small college this failure manifests itself in several forms. One is that we have an excellent learning opportunity going begging on our farm, and no way to take advantage of it. Despite the fact that we have numerous students at our small college that want to be livestock farmers, and despite the fact that numerous others wish to work in general sustainability and sustainable food systems in particular, the best the Womerippi teacher-farmers been able to manage this year is showing our slides of the birthing process in one or two classes.

We Womerlippis will really have to do better next year.

After years of advocacy, the college has made a start on livestock programming for the campus farm, and will soon begin operations, but there's a natural limit to what we'll be able to do on campus. Students need to learn to care for animals on campus, because then they have the opportunity to learn the constant daily care regime discipline.

This is the professional ethical imperative of the farmer and the zookeeper -- you have to be there for your animals. Hard experience has shown that this ethic is surprisingly hard to teach. Students need to learn daily care by doing it -- and by being held responsible.

But we won't be able to have examples of each and every kind of animal on the campus farm. We'll still need to take advantage of our local resources: MOFGA and local farms, as well as our own Unity College teacher-farmers.

Saturday, April 20, 2013

McKibben, Leggett and Stern all write on the carbon bubble

We just happened to talk about this problem in class only the other day.

Here's McKibben and Leggett, from the Guardian.

Here's the full report from Nick Stern's Grantham Institute.

Here's McKibben and Leggett, from the Guardian.

Here's the full report from Nick Stern's Grantham Institute.

Friday, April 19, 2013

What kind of problem is climate change?

This post comes about as the result of a classroom debate, in which the opposite of what is supposed to happen took place, which is that my students made me think, not the other way around.

(I probably made them think too, but I doubt that they're up at 2 am writing about it. But one of the things I like about my small college is that this kind of thing happens all the time.)

The question I posed for my students is this: What kind of problem is global climate change? Is it the kind of problem that could be solved by an activist movement? Or is it a different kind of problem with an entirely different kind of solution?

This bout of classroom- and self-questioning comes about because I became uncomfortable with the thinking behind the Keystone Pipeline protest, currently the focus of the most visible climate change movement, 350.org, and was foolish enough to say so in class. Most of the class was interested in my reasoning, but one particularly activist student was a little upset with me.

I'm not unsympathetic. I used to be a student activist. But I had planned a career in environmental research and education, focused on the economics and political economy of climate change. When it came time for the PhD dissertation, I chose to focus on investigating an earlier movement of climate activism that has now all but petered out (a dissertation topic that enabled me to combine my interest in activism with economics), and so it's natural for me to wonder whether the current movement is heading in the same direction. Indeed, my advisor at the time, Robert Sprinkle, forced me to consider whether or not that particular movement might not peter out, and wouldn't let me defend until I had included this consideration in the dissertation. At the time I was upset, but later I came to realize he was just doing his job -- training a biased thinker to be more of a critical thinker.

I also noticed that many, if not most, of the campaigns I worked on while an activist also petered out.

The problem with the Keystone Pipeline protest is that it is very symbolic, almost purely so. Even it's primary author, Bill McKibben, realizes this and has said as much in numerous editorials. (In one, he likens it to the symbolic Stonewall riot in gay rights history.)

Stopping the Keystone probably wouldn't reduce climate emissions in the long run. That would require reducing or stopping the use of tar sands. To be fair, this is McKibben's ultimate goal, along with the end of coal use and a massive reduction in the use of oil and gas.

But the Keystone may be a poorly chosen symbol, and quite a lot of important recent opinion, from business thinker Joe Nocera to philanthropist Jeremy Grantham, has said so. (These are people otherwise favorable to reducing climate emissions.)

The problem is, were the Keystone stopped, the Canadian and American oil companies operating in Alberta would find other routes to get their tar sands oil to market, and in fact are already doing so; indeed, they seem to be expecting to have to use multiple routes, which is not irrational considering their situation.

Put yourselves in their shoes for a minute, if you can. If you were the owner or senior executive in a Canadian pipeline company (if you were unscrupulous enough to accept that position in life) you'd have decided already that it was intolerable that American environmental activists could attack one of your projects so, and you'd be organizing to prevent that happening again. The solution is obviously to route the tar sands bitumen through Canadian lines to Canadian refineries.

Clearly, if American activists want to stop the use of Canadian tar sands, the Keystone is just the first part of a long battle, and quite a bit of that battle will ultimately take place in Ottowa. It is probably true that the Keystone outcome will set the stage for that more purely Canadian political conflict. But I'm not sure it goes much further than that.

Of course, lost symbols can still be important ones. John Muir's battle for Hetch-Hetchy valley in the early 1900s was just such a symbol. The reservoir was built, the valley drowned, but the movement (the Sierra Club) goes on.

I could go on, back and fourth, pros and cons. At the very least, it should be easy to see that the Keystone is questionable as a focus in the medium to long run. Ultimately we have to reduce emissions across the board, across a huge range of industries, and even across borders. We have to get the Europeans and the BRIC countries to go along with us in doing so. It's going to take a lot more thought and policy.

So, what if this problem is more generalizable. What if climate change just isn't the kind of problem that activism can easily deal with, at least at this historic stage? What if it's an entirely different kind of problem? More systemic, more embedded in our economic system, so intricately entwined with the way we make our living as to be very difficult to unwind?

If solving climate change requires this great unwinding of the use of fossil fuels, isn't it more a problem of technology adoption and transfer? Perhaps exacerbated by the need for a stiffer economic morality than is currently in vogue.

Let's look for analogies and comparisons.

One interesting case is that of the abolition of slavery. Slavery was a legal lifestyle choice in the thirteen American states at the time of the founding of the Republic. Likewise, it was legal in all the major European empires which at that time controlled a large part of the rest of the planet's land surface, as well as in China and the Islamic world.

Much like the use of fossil fuel is a legal lifestyle choice today, two hundred years ago, even on the farm in Maine where I'm currently writing this, slaveholding would have been legal and proper. Even American Quakers in post revolutionary Pennsylvania and Maryland often held slaves.

Even people that knew better, in other words.

To understand this, you need to understand a good deal more about the Anglo-American history of slavery than is usually taught in history classes. How could pre-Revolutionary war Quakers, often held up as exemplary New Testament, Sermon-on-the-Mount liberal Christians, accept slavery so easily? The answer is that black African-American slavery grew out of white indentured and penal servitude. Indentured servitude itself grew out of feudal serfdom. All were systems for organizing slave labor. Owning other people was a basic form of capital in the pre-industrial era across the western world and indeed across the planet. The other basic capital good was, of course, land. Both were needed to produce goods. Indeed, prior to the Enclosure Movement in British society, serfdom was the most common form of labor organization. It was the way things were done.

Early American Quakers, many of whom would have been indentured themselves at one point, accepted the use of indentures as an valid institution, a techno-legal system, for training apprentices and for organizing farm and industrial labor, and later, following the example of the Caribbean plantations, extended the system to forcible black Africa-American slavery. It was the eventual recognition that forcible, permanent, race-based slavery is a very different thing than an indenture that began the abolition movement. (It's ironic that only the advent of fossil fuels permitted the abolition of race-based slavery, and, eventually, white indentured servitude.)

In much the same way that the early Quakers accepted the economic facts of life unquestioningly, the Womerlippis, who clearly know better, still use some oil and gas.

Like those long-ago Quakers probably did, we assuage our consciences with the feeling that we've done as much as we can, as fast as we can, to reduce our dependence on the "peculiar institution" of fossil fuel. We live in a fully-retrofitted, super-insulated home that needs no oil for heating and has super-efficient appliances. My wife Aimee and I grow as much of our own food as we can, reducing food miles, and buy much of the rest from fair trade outlets. We long ago divested our retirement funds. We tend to buy very few new consumer goods, instead utilizing a lot of second-hand and repaired items, as well as fair-trade, home-made, or local products. We don't take fossil-expensive vacations, or fly much at all. And we both work in the sustainability movement, for a leading sustainability college. I even take some credit for introducing the idea of sustainability to little Unity College, many years ago.

We're not good candidates for fossil fuel bad guys.

But we are.

We still use oil and propane. A good deal less than most folk, than the average, but we use some.

This gets mildly technical. There remain two areas in which we have yet to divest ourselves of the need for fossil fuel. No fault of our own, we currently can't afford to buy electric cars. We also have a propane-based hot water heating system, albeit a super-efficient on-demand type. We can't afford a solar thermal system. We have to pay our house and student loans off first, before making these other purchases, and that's taking longer than it should. We do know better. Specifically, we know that despite our otherwise heroic efforts at living fossil-free, there are still some fossil-free technologies we need to adopt, but the pace at which we can adopt them remains limited by finances.

Does this make the Womerlippi's hypocrites? I think the answer has to be "yes," at least for now. I don't think you can meaningfully teach or research sustainability in the absence of a sustainable lifestyle. Never mind the morality, that we expect internal consistency from advocates. It just doesn't work. Students and the general public lose respect almost immediately they detect even mild hypocrisy, and so will then disbelieve almost everything else that person says.

Put another way, teaching is leadership, and in most cases, you have to lead from the front.

So, what to do? I'm no perfectionist, but this bothers me a good deal, and I've even considered building my own electric car, or running a diesel vehicle on waste oil, two solutions that I've helped students and friends with over the years. I tend to think if I did, I'd quickly run out of time for other enterprises I have to keep going, particularly my wind power research. And I doubt these self-help approaches would be cheaper in the long run. I have a long track history of spending too much family money on experimental fossil fuel-reduction schemes, such as the Bale House, my recent Land Rover project, our piggery, or our sheep farm. So far, I've decided to wait until we can afford a first-generation, second-hand Chevy Volt or a Nissan Leaf. This may take a while. I may utilize a second-hand Prius as a bridge to the fully electrical vehicle we nearly need, once I've gotten the maximum number of lifecycle-analysis efficient miles out of our old Ford wagon. I keep running the numbers in my head, and my current thinking is that I have perhaps twenty more thousand miles to go until the Prius, the first stage of the scheme. I think my wife appreciates my reticence.

I expect that there were a lot of Pennsylvania and Maryland Quakers in the mid- to late-1700s and early 1800s that felt much the same way about their slaves as I feel about our cars. The economized and moralized at the same time, and drew trade-offs between the two. They probably found all kinds of ways to explain to themselves why they had to continue to own other human beings. They needed them to run their farms and businesses. The slaves would be treated worse if they were released. The slaves were part of the family. They needed them for a comfortable retirement. It was the way things were done. If you're familiar at all with the history of the abolition movement, you've heard or read about these kinds of sentiments.

And of course, like the Womerlippis with their attempts to abolish their own fossil fuel dependency, those Pennsylvania and Maryland Quakers were "early adopters" of the new anti-slavery economic morality. The same ideas had to spread across a good deal of the northern part of the country, and then be the cause of a horrible civil war, before slavery was finally eradicated. And even now, even today, there's still an American slave trade, in trafficked women and children for sex, and in illegal migrant workers.

I don't think this analogy overblown. The use of fossil fuel robs our children and grandchildren of the ability to have a safe existence on planet earth. It makes them slaves to the misfortune of a deteriorating climate. One day it will be just as morally reprehensible to burn fossil fuel as it is to traffic modern slaves. One day, only criminals will do it, together with a very few enterprises licensed for the purpose by government.

But that day seems a long way off right now. Right now, most people think fossil fuel use a perfectly moral and proper lifestyle choice, much as many Americans felt about slavery in, say 1750.

By 1810 or 1820, most northerners knew race-based slavery was immoral, even un-Christian. Obviously, it took a good deal more time, and a civil war, to change the minds of a lot of southerners.

Abolition was, of course, an activist cause in its day. But long before the activism, there was this need for a moral and economic proof. Americans could live, and live well, without slaves. The first anti-slavery campaign in the United States was led by a Quaker, John Woolman, and consisted primarily of Woolman walking from one Quaker meeting to the next, explaining in very practical terms how to do without slaves.

In other words, Woolman explained how to do without the techno-legal concept that at that time was the primary method for organizing farm and industrial labor. Mostly, this meant paying a premium for free labor, or substituting labor-saving machinery. And indeed, just as with modern fossil-free technology, sometimes is was actually cheaper to do without slaves.

Woolman's ministry was in the 1750s and 1760s, much earlier than the rest of the abolition movement. The kind of activism we've come to expect, the John Muir, Bill McKibben type of campaigning for symbolic causes, the famous literature, the Uncle Toms, the Lovejoys, Frederick Douglas and Horace Greeley, the great symbolic campaigns, all that came later.

(Several decades later, actually, in the early 1800s, before the Civil War. We'll have to move faster on climate change. But I doubt the time-frame is an important part of the analogy.)

So slavery wasn't an activist type of problem, at least in the first few decades. It was a problem of legal, farming and industrial technicalities, particularly the legalities of how to organize labor. Morality was a driving force, but a techno-economic proof was first required. Without that, I tend to doubt there would have been much of an abolitionist movement at all.

If I'm right, then there needs to be more of the John Woolman kind of activism, a kind of evidentiary proof that humans can do just fine without fossil fuels. Ordinary Americans will need to realize that they can do without the inherent slavery of fossil fuel. We sustainability teachers have to lead from the front. We have to first demonstrate, then help everyone else imagine, a future where no self-respecting American family would be willing to do without an energy-efficient dwelling, an electric car, or a divested portfolio.

Seen in this light, 350.org's divestment campaign, of which Unity College is a major partner, is perhaps a better focus than the Keystone pipeline. Divestment sends a more purely moral message that travels better and lasts well.

Keystone instead, and all-too-easily, leads into a kind of pointless chess game in Canadian politics, where one side will try to out-manouver the other, probably for years to come.

(It also suggests that the Womerlippis may need to restructure their finances to be able to manage an electric car sooner rather than later.)

This analogy also points to a potential major problem within climate activism, a problem to be avoided at all costs. Slavery eventually became a sectional and geographical issue, leading to North versus South in the Civil War.

Currently climate campaigning seems much more visible and important in the northeast and western parts of the country. It's not that hard to imagine the south getting left behind in all this. The south also has a good deal of coal, oil and gas, and so more vested interests.

Kevin Philips wrote, in The Cousins' Wars, that the American Civil War was just a sequel to the Revolutionary war, which itself was a sequel to the British Civil War. In each case northern mercantile industrialists, clergymen, and educators were pitted against southern aristocrats and elitists. At stake were various northern definitions of freedom and liberty, versus vested southern economic interests. (For an early text in this continuing sectional Anglo-American conflict, I recommend the Putney Debates.)

Is that going to happen again, over oil, coal and gas?

I don't think the regions break out in quite the same way, considering there is also fossil fuel in Canada, New York and Pennsylvania, and North Dakota. But it's not hard to imagine that at the endgame, in ten or twenty or thirty years time, any last-ditch political effort to support fossil fuel will come from the south.

(I probably made them think too, but I doubt that they're up at 2 am writing about it. But one of the things I like about my small college is that this kind of thing happens all the time.)

The question I posed for my students is this: What kind of problem is global climate change? Is it the kind of problem that could be solved by an activist movement? Or is it a different kind of problem with an entirely different kind of solution?

This bout of classroom- and self-questioning comes about because I became uncomfortable with the thinking behind the Keystone Pipeline protest, currently the focus of the most visible climate change movement, 350.org, and was foolish enough to say so in class. Most of the class was interested in my reasoning, but one particularly activist student was a little upset with me.

I'm not unsympathetic. I used to be a student activist. But I had planned a career in environmental research and education, focused on the economics and political economy of climate change. When it came time for the PhD dissertation, I chose to focus on investigating an earlier movement of climate activism that has now all but petered out (a dissertation topic that enabled me to combine my interest in activism with economics), and so it's natural for me to wonder whether the current movement is heading in the same direction. Indeed, my advisor at the time, Robert Sprinkle, forced me to consider whether or not that particular movement might not peter out, and wouldn't let me defend until I had included this consideration in the dissertation. At the time I was upset, but later I came to realize he was just doing his job -- training a biased thinker to be more of a critical thinker.

I also noticed that many, if not most, of the campaigns I worked on while an activist also petered out.

The problem with the Keystone Pipeline protest is that it is very symbolic, almost purely so. Even it's primary author, Bill McKibben, realizes this and has said as much in numerous editorials. (In one, he likens it to the symbolic Stonewall riot in gay rights history.)

Stopping the Keystone probably wouldn't reduce climate emissions in the long run. That would require reducing or stopping the use of tar sands. To be fair, this is McKibben's ultimate goal, along with the end of coal use and a massive reduction in the use of oil and gas.

But the Keystone may be a poorly chosen symbol, and quite a lot of important recent opinion, from business thinker Joe Nocera to philanthropist Jeremy Grantham, has said so. (These are people otherwise favorable to reducing climate emissions.)

The problem is, were the Keystone stopped, the Canadian and American oil companies operating in Alberta would find other routes to get their tar sands oil to market, and in fact are already doing so; indeed, they seem to be expecting to have to use multiple routes, which is not irrational considering their situation.

Put yourselves in their shoes for a minute, if you can. If you were the owner or senior executive in a Canadian pipeline company (if you were unscrupulous enough to accept that position in life) you'd have decided already that it was intolerable that American environmental activists could attack one of your projects so, and you'd be organizing to prevent that happening again. The solution is obviously to route the tar sands bitumen through Canadian lines to Canadian refineries.

Clearly, if American activists want to stop the use of Canadian tar sands, the Keystone is just the first part of a long battle, and quite a bit of that battle will ultimately take place in Ottowa. It is probably true that the Keystone outcome will set the stage for that more purely Canadian political conflict. But I'm not sure it goes much further than that.

Of course, lost symbols can still be important ones. John Muir's battle for Hetch-Hetchy valley in the early 1900s was just such a symbol. The reservoir was built, the valley drowned, but the movement (the Sierra Club) goes on.

I could go on, back and fourth, pros and cons. At the very least, it should be easy to see that the Keystone is questionable as a focus in the medium to long run. Ultimately we have to reduce emissions across the board, across a huge range of industries, and even across borders. We have to get the Europeans and the BRIC countries to go along with us in doing so. It's going to take a lot more thought and policy.

So, what if this problem is more generalizable. What if climate change just isn't the kind of problem that activism can easily deal with, at least at this historic stage? What if it's an entirely different kind of problem? More systemic, more embedded in our economic system, so intricately entwined with the way we make our living as to be very difficult to unwind?

If solving climate change requires this great unwinding of the use of fossil fuels, isn't it more a problem of technology adoption and transfer? Perhaps exacerbated by the need for a stiffer economic morality than is currently in vogue.

Let's look for analogies and comparisons.

One interesting case is that of the abolition of slavery. Slavery was a legal lifestyle choice in the thirteen American states at the time of the founding of the Republic. Likewise, it was legal in all the major European empires which at that time controlled a large part of the rest of the planet's land surface, as well as in China and the Islamic world.

Much like the use of fossil fuel is a legal lifestyle choice today, two hundred years ago, even on the farm in Maine where I'm currently writing this, slaveholding would have been legal and proper. Even American Quakers in post revolutionary Pennsylvania and Maryland often held slaves.

Even people that knew better, in other words.

To understand this, you need to understand a good deal more about the Anglo-American history of slavery than is usually taught in history classes. How could pre-Revolutionary war Quakers, often held up as exemplary New Testament, Sermon-on-the-Mount liberal Christians, accept slavery so easily? The answer is that black African-American slavery grew out of white indentured and penal servitude. Indentured servitude itself grew out of feudal serfdom. All were systems for organizing slave labor. Owning other people was a basic form of capital in the pre-industrial era across the western world and indeed across the planet. The other basic capital good was, of course, land. Both were needed to produce goods. Indeed, prior to the Enclosure Movement in British society, serfdom was the most common form of labor organization. It was the way things were done.

Early American Quakers, many of whom would have been indentured themselves at one point, accepted the use of indentures as an valid institution, a techno-legal system, for training apprentices and for organizing farm and industrial labor, and later, following the example of the Caribbean plantations, extended the system to forcible black Africa-American slavery. It was the eventual recognition that forcible, permanent, race-based slavery is a very different thing than an indenture that began the abolition movement. (It's ironic that only the advent of fossil fuels permitted the abolition of race-based slavery, and, eventually, white indentured servitude.)

In much the same way that the early Quakers accepted the economic facts of life unquestioningly, the Womerlippis, who clearly know better, still use some oil and gas.

Like those long-ago Quakers probably did, we assuage our consciences with the feeling that we've done as much as we can, as fast as we can, to reduce our dependence on the "peculiar institution" of fossil fuel. We live in a fully-retrofitted, super-insulated home that needs no oil for heating and has super-efficient appliances. My wife Aimee and I grow as much of our own food as we can, reducing food miles, and buy much of the rest from fair trade outlets. We long ago divested our retirement funds. We tend to buy very few new consumer goods, instead utilizing a lot of second-hand and repaired items, as well as fair-trade, home-made, or local products. We don't take fossil-expensive vacations, or fly much at all. And we both work in the sustainability movement, for a leading sustainability college. I even take some credit for introducing the idea of sustainability to little Unity College, many years ago.

We're not good candidates for fossil fuel bad guys.

But we are.

We still use oil and propane. A good deal less than most folk, than the average, but we use some.

This gets mildly technical. There remain two areas in which we have yet to divest ourselves of the need for fossil fuel. No fault of our own, we currently can't afford to buy electric cars. We also have a propane-based hot water heating system, albeit a super-efficient on-demand type. We can't afford a solar thermal system. We have to pay our house and student loans off first, before making these other purchases, and that's taking longer than it should. We do know better. Specifically, we know that despite our otherwise heroic efforts at living fossil-free, there are still some fossil-free technologies we need to adopt, but the pace at which we can adopt them remains limited by finances.

Does this make the Womerlippi's hypocrites? I think the answer has to be "yes," at least for now. I don't think you can meaningfully teach or research sustainability in the absence of a sustainable lifestyle. Never mind the morality, that we expect internal consistency from advocates. It just doesn't work. Students and the general public lose respect almost immediately they detect even mild hypocrisy, and so will then disbelieve almost everything else that person says.

Put another way, teaching is leadership, and in most cases, you have to lead from the front.

So, what to do? I'm no perfectionist, but this bothers me a good deal, and I've even considered building my own electric car, or running a diesel vehicle on waste oil, two solutions that I've helped students and friends with over the years. I tend to think if I did, I'd quickly run out of time for other enterprises I have to keep going, particularly my wind power research. And I doubt these self-help approaches would be cheaper in the long run. I have a long track history of spending too much family money on experimental fossil fuel-reduction schemes, such as the Bale House, my recent Land Rover project, our piggery, or our sheep farm. So far, I've decided to wait until we can afford a first-generation, second-hand Chevy Volt or a Nissan Leaf. This may take a while. I may utilize a second-hand Prius as a bridge to the fully electrical vehicle we nearly need, once I've gotten the maximum number of lifecycle-analysis efficient miles out of our old Ford wagon. I keep running the numbers in my head, and my current thinking is that I have perhaps twenty more thousand miles to go until the Prius, the first stage of the scheme. I think my wife appreciates my reticence.

I expect that there were a lot of Pennsylvania and Maryland Quakers in the mid- to late-1700s and early 1800s that felt much the same way about their slaves as I feel about our cars. The economized and moralized at the same time, and drew trade-offs between the two. They probably found all kinds of ways to explain to themselves why they had to continue to own other human beings. They needed them to run their farms and businesses. The slaves would be treated worse if they were released. The slaves were part of the family. They needed them for a comfortable retirement. It was the way things were done. If you're familiar at all with the history of the abolition movement, you've heard or read about these kinds of sentiments.

And of course, like the Womerlippis with their attempts to abolish their own fossil fuel dependency, those Pennsylvania and Maryland Quakers were "early adopters" of the new anti-slavery economic morality. The same ideas had to spread across a good deal of the northern part of the country, and then be the cause of a horrible civil war, before slavery was finally eradicated. And even now, even today, there's still an American slave trade, in trafficked women and children for sex, and in illegal migrant workers.

I don't think this analogy overblown. The use of fossil fuel robs our children and grandchildren of the ability to have a safe existence on planet earth. It makes them slaves to the misfortune of a deteriorating climate. One day it will be just as morally reprehensible to burn fossil fuel as it is to traffic modern slaves. One day, only criminals will do it, together with a very few enterprises licensed for the purpose by government.

But that day seems a long way off right now. Right now, most people think fossil fuel use a perfectly moral and proper lifestyle choice, much as many Americans felt about slavery in, say 1750.

By 1810 or 1820, most northerners knew race-based slavery was immoral, even un-Christian. Obviously, it took a good deal more time, and a civil war, to change the minds of a lot of southerners.

Abolition was, of course, an activist cause in its day. But long before the activism, there was this need for a moral and economic proof. Americans could live, and live well, without slaves. The first anti-slavery campaign in the United States was led by a Quaker, John Woolman, and consisted primarily of Woolman walking from one Quaker meeting to the next, explaining in very practical terms how to do without slaves.

In other words, Woolman explained how to do without the techno-legal concept that at that time was the primary method for organizing farm and industrial labor. Mostly, this meant paying a premium for free labor, or substituting labor-saving machinery. And indeed, just as with modern fossil-free technology, sometimes is was actually cheaper to do without slaves.

Woolman's ministry was in the 1750s and 1760s, much earlier than the rest of the abolition movement. The kind of activism we've come to expect, the John Muir, Bill McKibben type of campaigning for symbolic causes, the famous literature, the Uncle Toms, the Lovejoys, Frederick Douglas and Horace Greeley, the great symbolic campaigns, all that came later.

(Several decades later, actually, in the early 1800s, before the Civil War. We'll have to move faster on climate change. But I doubt the time-frame is an important part of the analogy.)

So slavery wasn't an activist type of problem, at least in the first few decades. It was a problem of legal, farming and industrial technicalities, particularly the legalities of how to organize labor. Morality was a driving force, but a techno-economic proof was first required. Without that, I tend to doubt there would have been much of an abolitionist movement at all.

If I'm right, then there needs to be more of the John Woolman kind of activism, a kind of evidentiary proof that humans can do just fine without fossil fuels. Ordinary Americans will need to realize that they can do without the inherent slavery of fossil fuel. We sustainability teachers have to lead from the front. We have to first demonstrate, then help everyone else imagine, a future where no self-respecting American family would be willing to do without an energy-efficient dwelling, an electric car, or a divested portfolio.

Seen in this light, 350.org's divestment campaign, of which Unity College is a major partner, is perhaps a better focus than the Keystone pipeline. Divestment sends a more purely moral message that travels better and lasts well.

Keystone instead, and all-too-easily, leads into a kind of pointless chess game in Canadian politics, where one side will try to out-manouver the other, probably for years to come.

(It also suggests that the Womerlippis may need to restructure their finances to be able to manage an electric car sooner rather than later.)

This analogy also points to a potential major problem within climate activism, a problem to be avoided at all costs. Slavery eventually became a sectional and geographical issue, leading to North versus South in the Civil War.

Currently climate campaigning seems much more visible and important in the northeast and western parts of the country. It's not that hard to imagine the south getting left behind in all this. The south also has a good deal of coal, oil and gas, and so more vested interests.

Kevin Philips wrote, in The Cousins' Wars, that the American Civil War was just a sequel to the Revolutionary war, which itself was a sequel to the British Civil War. In each case northern mercantile industrialists, clergymen, and educators were pitted against southern aristocrats and elitists. At stake were various northern definitions of freedom and liberty, versus vested southern economic interests. (For an early text in this continuing sectional Anglo-American conflict, I recommend the Putney Debates.)

Is that going to happen again, over oil, coal and gas?

I don't think the regions break out in quite the same way, considering there is also fossil fuel in Canada, New York and Pennsylvania, and North Dakota. But it's not hard to imagine that at the endgame, in ten or twenty or thirty years time, any last-ditch political effort to support fossil fuel will come from the south.

Friday, April 12, 2013

Letter to a former student about Margaret Thatcher's economic legacy

Hey Mick,

So I thought I would give you a little reprieve from my nagging questions, but as Margaret Thatcher just died, I can't hold them back any longer.

My first question; is The Economist a conservative publication?

My second question is more geared towards your opinion. I am in the middle of the article the Economist wrote about Thatcher. I know your general opinion of Thatcher, or at least I think I know it. The Economist has credited her with creating an 'ism' theory-Thatcherism. Matching its popularity with Keynesian economics. My real question here is-do people see Thatcherism as on the same level with Keynes economics? Did Thatcher bring the UK economy back from imminent peril? If a liberal had become PM instead of Thatcher and that PM had used Keynes economics instead of conservative economics, would the UK economy have come back?

XXXX

Dear XXXX

It's argued by neo-liberal economists (i.e., neo-conservatives who believe in market "freedom") that the combination of industrial stagnation (slow growth) and inflation in the mid-to-late 1970s in both Britain and the US was caused by Keynesian policies dating back to WW2, and immune to normal Keynesian stimulus.

In particular they blame the high upper income bracket tax rates then in place in both countries.

I see this as an excuse. We don't really know if a serious Keynesian stimulus would have worked, because none was tried, at least not until Reagan's military spending later in the 1980s.

Thatcher and Reagan certainly used the ensuing crises, particularly various catastrophic strikes, as well as public fear of the Soviet Union, and, in Thatcher's case, the Falklands War, to justify their neo-liberal policies and distract the populace while they ran down the public and manufacturing sectors of the economy.

Keynes' wasn't alive, so we don't know what he would have said. But neither Reagan and Thatcher's neo-liberal economic policies worked that well. Thatcher certainly rejuvenated the City of London (Britain's Wall Street), which became a glittering hub of global finance to an extent never previously imagined. But she did so by essentially abandoning all Britain's great industrial cities, including my home town of Sheffield.

Millions of British people have lived far worse lives as a result, with fewer services, low-wage jobs or no jobs, and rising economic insecurity, crime, delinquency, and the loss of culture. You could say that she "financed" British economic recovery, economically and politically speaking, by running down manufacturing cities in the north of England and in the Celtic British countries (Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland).

Especially after the catastrophic miners strike of 1984, with the unions out of the way, she was able to cut taxes on the rich and bring in Arab sheiks and Russian oligarchs to sponsor London's glitter, while ordinary people in ordinary cities lived with fewer services and no jobs for decades.

Reagan found it hard to pull out of the depression even with his lower taxation policy, and so the American manufacturing sector also began to decline sharply, until he began to reinvest in the US military. This is actually a Keynesian policy. Some call it "militarized Keynesianism", the only kind of Keynesianism you can get an American conservative to like.

Neither recession really ended until after the first Gulf War, with the so-called "dot com" bubble. The new technology, which was primarily American-led and American-owned, gave the US an economic advantage globally or the first time in a generation. Britain followed along in the US wake, providing a funnel for finance for the boom. Bill Clinton and Tony Blair reaped the reward, a short period of prosperity and budget surpluses in the mid 1990s. This came to an end with 9/11 and the bursting of the dot com bubble, after which manufacturing even in technology fled to China.

You have to give Margaret Thatcher credit for standing up against the Argentine dictators, when they invaded the Falklands, and against the PIRA, who almost killed her in the Brighton hotel bombing. She and Reagan also stood up against the Soviet Union, and so were partly responsible for the fall of communism. I do feel that Margaret Thatcher truly believed she was fighting for democracy and the rule of law.

But I think their economic record is a mixed bag, not at all the clear cut case that US neo-liberals like to make out, and recovery, when it finally came, was as much about technological change and military spending as it was about neo-liberal theory.

The loss I feel the most of all, and the loss that prompted me to leave the Royal Air Force in protest in 1985, was the loss of the northern and Celtic Fabian and communitarian ethic. Prior to Thatcher we had a rich heritage in the north and west of self-help Fabianism, unionism, cooperative societies and community spirit. Labour activists and Fabians in my family, particularly my grandfather GW Womersley, helped plan out the rebuilding of Britain after World War II. You should see the public housing estate my grandfather helped plan, in Dronfield, in the late 1940s and early 1950s. It's beautiful to this day, a model of community development, and a great improvement on the capitalist-owned slum housing prior to the war, much of which was bombed. My cousin (third or fourth) Malcolm Muggeridge, a BBC talk-show personality, was also a very successful spokesperson for this point of view. They represented a culture of decency and respect for the working woman and man that has now been lost to history, and supported the rebuilding of the northern and western communities that Thatcher's policies destroyed.

Thatcher and her ilk confused Fabianism with communism. But Muggeridge fought communism his whole life. He actually blew the whistle on Stalin as early as the 1930s.

So in general I think it unfair to credit Thatcher with any real economic achievement, except perhaps to set the stage for the failure of our most recent hyper-capitalist system during the Great Recession.

While one thing she did achieve was to undo the simply marvelous economic achievements of the earlier generation of Fabians, who rebuilt Britain after the war.

A very cheap victory, if anyone is foolish enough to even think it a victory.

Enjoy,

Mick

PS: The Economist can be conservative in the sense that we all sound conservative when explaining supply-demand realities. But mostly, it's just intelligent about economics.

Thursday, April 11, 2013

Maggie! (For class tomorrow)

By special request, we're going to discuss the legacy of former UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Like a lot of working class and northern or celtic-heritage Britons, I have extremely mixed feelings about her.

She stood up for democracy against the Argentinian Junta, the Soviets and the PIRA, but gutted the industries and communities of the north of England, Scotland and Wales.

And a little of the appropriate sound track, just for good measure...

She stood up for democracy against the Argentinian Junta, the Soviets and the PIRA, but gutted the industries and communities of the north of England, Scotland and Wales.

And a little of the appropriate sound track, just for good measure...

Summer job: good resume-builder!

Island Institute

Energy for ME

Position Opening: Youth Activities Coordinator

The Island Institute is

seeking Youth Activity Coordinators to participate in the implementation of the

Energy for ME Summer Institute (July 28 through August 2, 2013) to be held at the

Schoodic Education and Research Center in Winter Harbor, Maine.

Energy for ME is an energy

education program of the Island Institute, involving ten island and coastal

communities. Students in grades 6-12 – and their families – are learning how to

better understand their communities’ energy-consumption habits, and

implications, as well as how to develop effective strategies to increase energy

efficiency. To do so, they are using eMonitor energy meters to measure

electricity usage at several different access points, including homes, schools

and public buildings.

Based in Rockland, Maine the Island Institute is a

non-profit organization that has served for over twenty-five years as a voice

for the balanced future of the islands and waters of the Gulf of Maine. We are

guided by an island ethic that recognizes the strength and fragility of Maine's

island communities and the finite nature of the Gulf of Maine ecosystems. Along

the Maine Coast, the Island Institute seeks to:

·

Support the islands' year-round

communities;

·

Conserve Maine's island and marine

biodiversity for future generations;

·

Develop model solutions that balance

the needs of the coast's cultural and natural communities;

· Provide opportunities for discussion over responsible

use of finite resources, and provide information to assist competing interests

in arriving at constructive solutions.

Job Description

Position responsibilities

are:

- Assist in providing student leadership and community organizing training for students

- Provide student participants with activities for evening and open times

- Collaborate with Island Institute staff to create a schedule for students activities

- Mentor students on career and college aspirations where appropriate

- Support Island Institute trainers and coordinators as needed

Job Requirements

The successful candidate must

have the ability to work well with a team and follow through on assignments in

an accurate and timely manner. It is

important for this person to communicate and work effectively with a wide array

of individuals and be able to prioritize and handle numerous functions within

an effective workflow. This position will

require overnight stays at the Schoodic Education and Research Center (SERC) in

Winter Harbor, Maine during the nights of July 28, 29, 30, 31 and August 1,

2013 and to be available throughout each day beginning at 11:00 a.m. July 28 and

ending at 2:00 p.m. on August 2.

Education Requirements

The ideal candidate will have

past experience with middle and high school students in a camp setting. First aid certification is highly

recommended.

Compensation

This position offers free

room and board at SERC during the Energy for ME Summer Institute. A $500 stipend will also be provided.

Please submit applications

and/or questions to: Sally Perkins, Island Institute Programs Associate

PO

Box 648

Rockland,

ME 04841

Email:

sperkins@islandinstitute.org

Phone:

(207) 594-9209 ext. 103

Applications must be

submitted by May 15th, 2013

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Two must-reads

Another McKibbon-Keystone editorial in which he ramps up the rhetoric greatly.

And an interesting article on the world's shifting wine regions, as climate changes, with excellent maps.

And an interesting article on the world's shifting wine regions, as climate changes, with excellent maps.

Saturday, April 6, 2013

Pie-eyed

The Great Senior Gift Pie Shoot-off yesterday was a roaring success, especially for the fake whipped creme industry. Here the esteemed Doctor Phillippi gets a fine face-full.

I hear however, that the "creme" wasn't organic and contained GMO foods.

Here is my wonderful spouse again, making sure I too get a good face-full. Should have drafted that pre-nup, but it's too late now. Way too late.

I believe that is Ms. Barnes there, taking the shot. I hate to say it, but it's a very good shot.